Ad Astra: Achilles: The Brightest Star of His Age

“The aged Priam was the first of all whose eyes saw him as he swept across the flat land in full shining, like that star which comes on in the autumn and whose conspicuous brightness far outshines the stars that are numbered in the night's darkening, the star they give the name of Orion’s Dog, which is brightest among the stars, and yet is wrought as a sign of evil and brings on the great fever for unfortunate mortals.”[1]

Homer’s invocation of the star Sirius to describe Achilles in battle would have had weighty meaning for ancient listeners. Known today as Sirius A, it is the brightest star in the night sky and its name in Greek translates to “glowing” or “scorcher.” While today the star has a yellowish white colour, there is evidence that it may have been a brilliant red as recently as 2,000 years ago.[2]

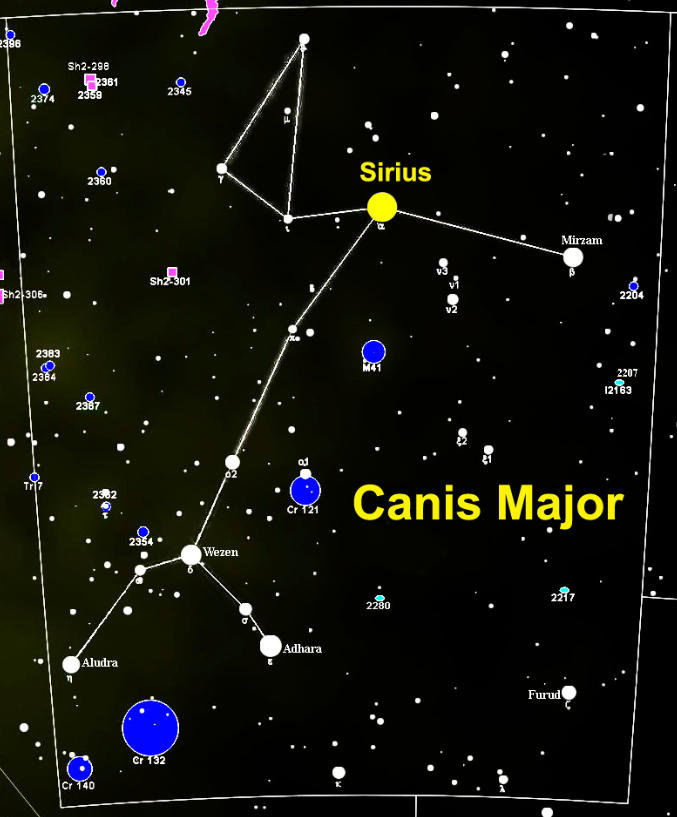

Part of the constellation Canis Major, it is the larger of two dog stars that accompanies the hunter Orion as he journeys across the sky. Its movements were tracked by almost all ancient cultures including the Greeks, Egyptians, Babylonians, Polynesians, Dogons, Sumerians, and Chinese, and figures heavily in many of their myths.

Once a year, Sirius experiences a heliacal rising: an annual event when the star is visible in the sky before sunrise. This occurs every year in early July after a two-month period of disappearance, when the star is too close to the Sun to be visible on Earth.

To the ancient Egyptians, the star’s reappearance coincided with the annual flooding of the Nile and was a herald of the New Year. The Egyptians worshipped the star as the chthonic fertility goddess Sopdet, an important mother goddess whose movements some historians believe were the basis of the solar civic calendar of the Egyptian state.

In contrast, the Greeks had a less favourable view of the heliacal rising of Sirius.

Its zenith coincided with supremely hot temperatures in Greece that were not tempered by the flooding Nile and welcomed in the famous “dog days of summer.” Hesiod in his Works and Days said this period was when “women are most wanton, but men are feeblest, because Sirius parches head and knees and the skin is dry through heat.”[3] Citizens were warned to stay indoors and hide from the hot weather and the wandering hordes of rabid dogs that were said to appear during this period. Once the “dog days” had diminished, farmers would return to the fields and begin picking grapes for the annual grape harvest.

Homer, master of simile and metaphor, made a powerful choice when evoking this star in describing the hero Achilles. His Greek listeners would have undoubtedly known that comparing Achilles to Sirius was effective shorthand for both the hero’s exceptionalism and brutality. Evoking the infamous burning star in describing his war path would have conjured up deeply rooted feelings of wonder, fear, and respect in listeners who had been conditioned to fear the chaos of the “dog days of summer.”

Only in recent times has this comparison lost its punch, as the post-Industrial world with its urban living and light pollution has robbed modern readers of this longstanding connection with the stars. By adding back this context, modern readers can hope to experience this line of text the same way humans have understood it for thousands of years.

Sirius A

[1] Homer, and Richmond Lattimore. The Iliad of Homer; Translated with an Introduction by Richard Lattimore. University of Chicago Press, 1962. [2] D. C. B. Whittet, A physical interpretation of the ‘red Sirius’ anomaly, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 310, Issue 2, December 1999, Pages 355–359, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-8711.1999.02975.xTop of FormBottom of Form [3] Hesiod, and Hugh Evelyn-White. The Theogony of Hesiod and Works and Days. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2011.