Ancient Athletics Part Two: Get With the Programme

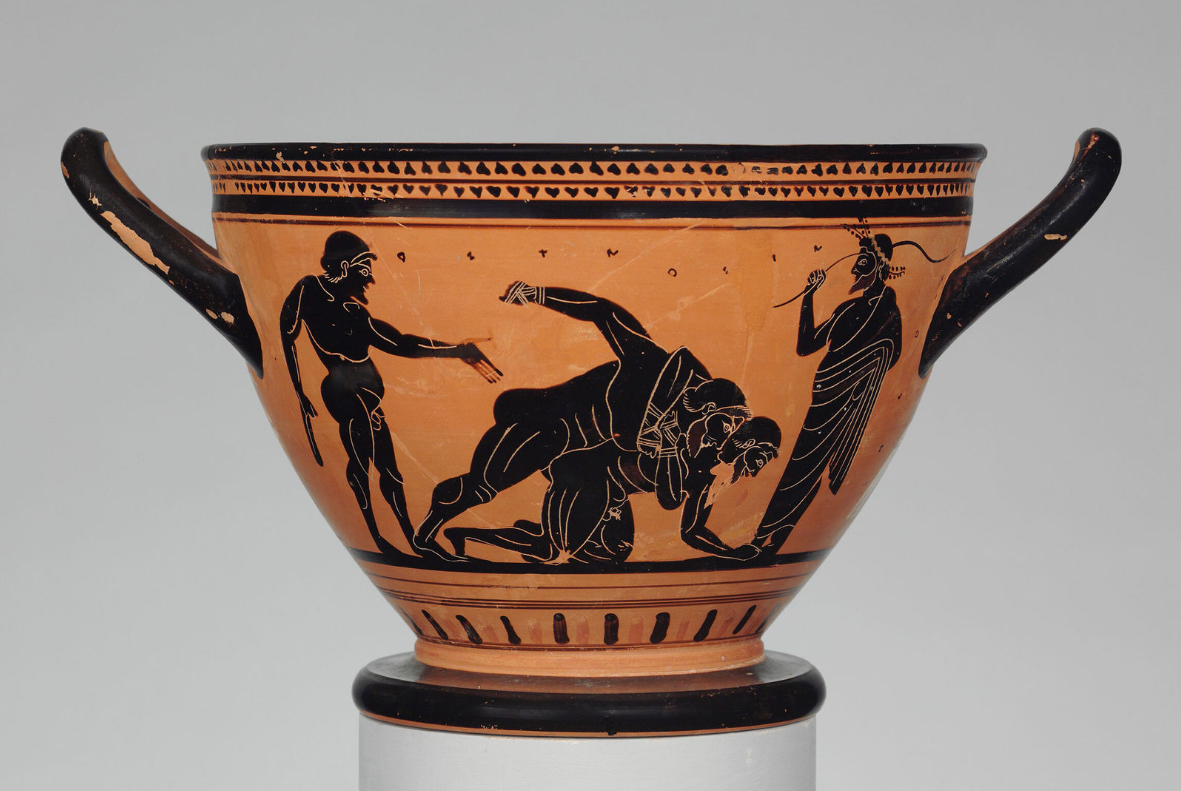

Terracotta skyphos (deep drinking cup), ca. 500 B.C. Greek, Attic. Attributed to the Theseus painter. Terracotta, 6 ½ × 9 in. (16.2 × 22.5 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, Rogers Fund, 1906 (06.1021.49)

The Paris 2024 Games have 329 medal events running simultaneously in multiple locations.The program has been carefully masterminded to fit it all in. The ancient Games didn’t have this problem, because no events ran concurrently and the entire festival took less than a week. Despite this, nobody really knows the running order of events and ceremonies, because no detailed descriptions of the program survive. Scholars have had to construct plausible programmes of contests, ceremonies and feasts based on the fragmentary evidence available. We can only make educated guesses, around a few events that we know were fixed. The festival grew longer over time as more events were added, and as events for youths were introduced. What started out as a single race grew into a festival of track events, combat sports and equine races, complete with semi and perhaps quarter finals. We do know that events were largely scheduled by type.

What follows is an approximation of the festival programme in 200 BCE (the final year that a new event was added.)

Before the Festival

The Olympic Truce began on the first full moon after the summer solstice. All athletes had to register at Elis (the city that organised the Games) on this day, to begin their final training under official supervision, and for preliminary knock-out rounds that ensured that only the very best athletes would compete at the festival itself.

For everyone else, the truce paused all warfare, and attendees travelling to the sanctuary during this time were considered religious pilgrims and were not to be harmed. All legal disputes were put on hold, and executions had to wait until the truce was lifted.

The Eve of the Festival

Two days before the Games began, the athletes and officials set out from Elis and travelled on foot to the sanctuary, some 37 miles away. They’d arrive as night fell on the eve of the first day. We can imagine the avid sports fans trying to arrive early to get a good view of their favourite superstars. This was the final opportunity to get a good camping spot, too. Some forty thousand Greeks would descend on the sanctuary for the festival, and they had nowhere to stay. So, tents of all sizes would start popping up around the outside of the altis (the official sanctuary zone) in the days before the festival. I imagine that prime spots would be close to the tents of sporting celebrities, and by the river, which was the sole source of water until the 2nd century CE. Merchants would also be setting up stalls; you could buy anything you needed or had forgotten at home. You could also buy raw ingredients if you fancied cooking your own dinners (which meant lugging braziers and pots across the Mediterranean) or prepared food from a myriad of stalls (consider Olympic catering to be the forerunner of food trucks.)

Day One

As a religious festival, proper deportment and respectful conduct was expected. On the first day, all athletes, coaches and judges visited the Bouleuterion. Slices of boar meat were laid out and the athletes would first swear that for the ten months prior to the Games, they had trained following the official regulations. Then, they swore to obey the rules for the duration of the festival. Their trainers and coaches were also required to swear oaths that no cheating would occur. Finally, the Hellanodikai (judges) would swear to refuse all bribes, to judge the athletes fairly and to assign them to the correct competitive age categories. The Hellanodikai were responsible for drawing the lots of competitors, so it must have been very tempting for anxious athletes like wrestlers and boxers to slip a judge some coins to be ‘randomly’ assigned a weaker opponent. Like the athletes, the judges would be harshly fined for breaking the rules. Amusingly, Pausanias admits that he can’t remember what happened to the boar meat, just that he doubts it was cooked and eaten. Even the best tour guides forget something now and again. The participants then made offerings to the gods at the many altars around the sanctuary.

From 396 BCE onwards, there were contests for the trumpeters and heralds. Until that point, they’d always been recruited from Elis, but why not add even more competition? This needed to be the first contest, because the victors would be incredibly busy for the next week. The trumpeters would perform fanfares to get the crowd’s attention for the herald to make announcements: every athlete had to be announced so that spectators knew who was who, so the herald would introduce each athlete by his name and city. The role of herald required peerless volume, tone, diction and breath control, because they weren’t allowed to take a breath halfway through a pronouncement.

Having heard a lot of fanfares and bellowing, hundreds of small cooking fires were lit as hundreds of thousands of spectators got ready for dinner and a night beneath the stars.

Day Two

In the earlier centuries, the pentathlon had to share a day with the equestrian events. The problem was that both took a long time, so eventually the second day was devoted to the pentathlon alone. The five events began with the javelin, discus and long jump (but we don’t know the order of these first three events) followed by a sprint from one end of the stadium track to the other, and finally wrestling to finish.

Day Three

By 200 BCE, day three was likely devoted to equestrian events. The crowds trooped into the hippodrome for a day of all things equine. There were chariot races as well as horseback riding, and these races were fast and furious. Only the rich could afford to breed, train and transport horses and buy chariots, so this was the day when aristocrats won events. Not that they left their seats, of course; equestrian events could be dangerous and even deadly, so aristocrats owned enslaved people and trained them as drivers and jockeys. Naturally, the aristocrats received the crowns and glory, and we don’t even know the names of the jockeys.

Day Four

The middle of the festival saw a pause in contests to allow for the very sacred rites necessary for such a religious occasion. The day started with a rites to Pelops, one of the mythical founders of the festival. This took place at the Pelopion, close to the Temple of Zeus and enclosed with a wall and planted with trees. Here, at his (supposed) tomb, priests sacrificed a black ram and poured its blood into a pit. This libation was to invite Pelops to join in the next part of the day.

A sacred procession from the Prytaneion to the Altar of Zeus. Athletes had been making their own offerings already, but this was a communal sacrifice. The procession was led by the Hellanodikai wearing their official purple robes. Then came priests, leading a hundred oxen. They were followed by ambassadors from all of the Greek cities, then the athletes and their coaches. The altar of Zeus was unusual in that it was covered in a mound of impacted ash collected from previous sacrifices, and as such got bigger and bigger with each Olympiad. The altar stands on a spot marked out by Zeus sending a bolt of lightning.

A pyre was constructed of white poplar wood, and set alight. The oxen were ritually slaughtered and prepared for the fire. The thighs were burnt so that the gods could enjoy the smoke, and the rest of the meat was portioned up for cooking and distributing to the people present as part of a sacred feast. This kind of sacrifice of a hundred oxen was called a hecatomb, and was an incredibly ostentatious (and expensive) gift to the gods. This was the religious centrepiece of the entire festival.

After a festive communal feast with lots of wine, it was time to head into the stadium to resume the athletic events. Some events had a youth category, The youngest victor we know of is Damaskos of Messene, who won the youth stadion at the age of 12, likely the first year he was eligible to compete. The boys would graduate to the men’s events aged around 18. There weren’t many events open to boys, as some were deemed too dangerous. They could run the stadion sprint and wrestle from 632 BCE, box from 616 BCE and from 200 BCE, the final event added to the Games, they could even partake in pankration. In 628 BCE a boys’ pentathlon was held but immediately dropped from the program.

Day Five

The fifth day was the big one. Scholars think track events happened in the morning, including sprints and long distance races. Then in the afternoon came contact sports, including the brutal pankration. This was the day when spectators could hope to see a triastes, or a triple win. That happened when a single man won three of the four footraces, or all three contact sports. Achieving a triple was rare, so the crowds must have gone absolutely wild when it did happen. This was also the day when the stadion winner was decided; as the oldest and most prestigious event at the festival, the winner became an instant celebrity.

We’re told the final event was the hoplitodromos, the race in armour. Some scholars think that such a military event was symbolic of the end of the sacred truce, so that Greeks could soon get back to their favourite activity (squabbling).