Ancient Games: Elysium (2015)

· Alex Imrie

·

·

o Sep 4, 2021

o

o 7 min read

Updated: Sep 26, 2021

The Backdrop

In the sixth book of Virgil’s Aeneid, the poet recounts Aeneas’ journey to the underworld. During this voyage, the destiny of Rome is revealed to him by his dead father, Anchises. Assisting in this journey was the Cumaean Sibyl, who distinguished between the path to Elysium and the dread realm of Tartarus:

Night approaches, Aeneas: we waste the hours with weeping.

This is the place where the path splits itself in two:

there on the right is our road to Elysium, that runs beneath

the walls of mighty Dis: but the left works punishment

on the wicked, and sends them on to godless Tartarus. (6.539-45, tr. Kline)

Upon arriving in the underworld, the Sibyl identifies the figure of Musaeus of Athens, and asks him where Anchises might be found. In his response, the spirit described the nature of Elysium itself:

None of us have a fixed abode: we live in the shadowy woods,

and make couches of river-banks, and inhabit fresh-water meadows.

But climb this ridge, if your hearts-wish so inclines,

and I will soon set you on an easy path. (6.670-74, tr. Kline)

'Elysian Fields' by Carlos Schwabe (1903)

On one level, this journey beyond the mortal coil serves as a vehicle for Virgil to infer Rome’s supposedly manifest destiny, in a similar fashion to the Jovian prophecy of ‘power without limits and empire without end’ (1.353-54) found in the opening book of the work. Whether we choose to read the Aeneid as a full-on propaganda piece or a subtly-played subversion of the nascent Augustan Principate, one feature that remains constant is Virgil’s idyllic presentation of the Elysian Fields.

The picture of Elysium as a pleasant and sheltered realm in perpetual spring is not unique to the Aeneid, with similar imagery of a blissful paradise found in the writing of Homer (whom Virgil follows), Hesiod and Pindar, to name a few. Distilled through multiple sources between antiquity and modernity, Elysium still pervades popular culture in myriad forms: from Mozart’s Magic Flute to Hollywood blockbusters. In film, it has been an ethereal yet fertile landscape in Gladiator (dir. Scott, 2000) to a utopian space station more recently, in the otherwise dystopic Elysium (dir. Blomkamp, 2013). The verdant tendrils of the Elysian fields also reached the realm of board-gaming in 2015 with the imaginatively named (you’ve guessed it…) Elysium.

The Game

- 2-4 Players - 45-60mins

- Age: 14+ -Publisher: Space Cowboys

Designed by Brett Gilbert and Matthew Dunstan, Elysium is a game of gods and monsters in which players assume the role of ambitious demigods competing to earn a place for themselves on Mt. Olympus. The game is played over five rounds (‘epochs’) and the player with the most Victory Points (VPs) after the final round is declared the winner.

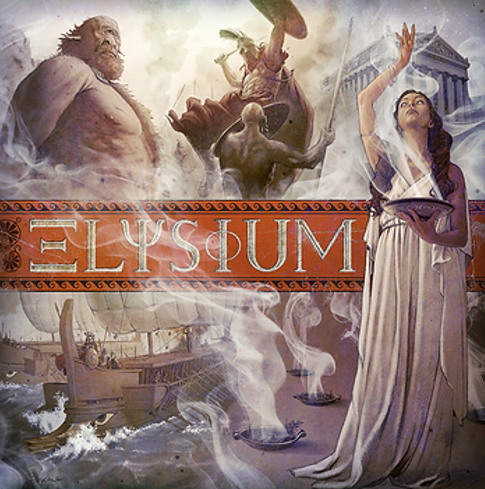

Box Art for Elysium (2015)

Before getting into how the game works, we need to talk about the box art… I don’t normally spend too much time deconstructing the box, but it is worth doing here. Starting with the negative: any classicist with a smidgeon of Greek will immediately notice how the graphic designers have rather butchered the titular text. In an attempt to add a touch of Hellenic mystique to their box, in the best traditions of the Nike brand, the title proudly proclaims in all-caps, ‘XLPSFUM’. Doesn’t have quite the same ring.

On to the positive. The box art is stunning, giving the player a real sense of the divine theme underpinning the game. A priestess is engaged in some mysterious rite, eyes rolled back and divining images of triremes, hoplites and a cyclops, no less. This brings us to the box insert, yes, the box insert. Here, the designers have gone above and beyond, evoking the front aspect of a Greek temple! How cool is that?!

How do you play Elysium?

On first sight, the setup might seem a bit overwhelming but, once you have a handle on the components, everything falls neatly into place.

Players begin by assembling a player board which is divided into areas to house all the components: VPs, Prestige Points, Money and Action Markers (shaped like little columns!) It also comes with a slot to accommodate a token to denote your position in the order of play, something which can change after every epoch.

The player board performs another important function, dividing your play area into an upper and lower level: your Domain and your Elysium. During each epoch, you will draw cards that contain different skills and VPs into your Domain. Later, you will have the chance to move some of these into your Elysium. And herein lies the (amazing) rub… the abilities on cards will only function when in your Domain, but only score you VPs in your Elysium. This elegant binary means that players are constantly forced to balance between receiving in-game abilities and end-game points. It’s a simple mechanic, but one which can get fiendishly tricky as you try to work out the relative value of a card to your game in any given turn.

Going back a step, in order to get these cards, players take them from a central play area, referred to as the Agora. At the start of the game, players randomly determine a set of five suits (Olympian Gods) to play with, each with particular emphases: Poseidon is an aggressive player-to-player attack deck, while Hephaestus offers players the chance to amass money, for example.

Players can’t just take whatever they like, though: they must have the relevant Action Markers on their player board. In the top right corner of each card is their cost. Players need either one or two symbols to be able to take the card in question. After a card is taken, the player must then discard one of their Action Markers, limiting the cards that they will have access to in subsequent rounds. Timing and knowing when to sacrifice your Action Markers are the keys to winning, here. If a player finds themselves unable to take a card normally, they must take a ‘Citizen’ card (which functions as a wild card in play, but carries a VP penalty at the end of the game).

Example of a 3-Player setup

An added complication here is the ‘Quest Tiles’. These are taken in the same manner as other cards and are important in two ways: 1) dictating player order, and 2) giving varying levels of Money, VPs and ‘Transfers’, the mechanism through which cards can be sent to the Elysium. Each player must take one Quest per epoch; if a player is unable to do so, then they must take a ‘Failed Quest’, with drastically reduced points and abilities.

So how to these cards actually score you points?

Once the cards are in your Elysium, they are considered ‘Legends’ (effectively melds of cards). There are two types of Legend which players can score with: 1) Level Legends: comprising cards of the same numerical value but from different Gods, and 2) Family Legends: comprising cards from the same God, but with ascending numerical values. The difficulty here is that you may not move cards between Legends, so once you have committed to one of the two types, you are committed until the end of the game.

Final scoring is completed after the fifth epoch, with the player possessing the largest number of VPs achieving victory and getting to take their rightful place on Olympus!

The Review

This was the first game that I bought purely on the basis of its ancient theme. Ironically, after purchasing it, the initially bewildering array of tokens deterred me from getting it to the table for a while. This is now a major regret, since I have thoroughly enjoyed every game of Elysium that I’ve played since cracking it open. I always get an addictive feeling of excitement tinged with outright frustration! At the start of the game, five epochs feels like… well… an epoch away! By the end of the third round, though, the end of the game always seems to be running towards you like Pheidippides! I love that the game challenges you to craft an efficient engine, then forces you to break that very same engine in order to score points.

The components are well-made and tactile on the whole. The card texts are well-written, meaning that there is very little ambiguity about what each card actually does in-game (although the instruction manual is also helpful in times of confusion). It’s also not the heaviest of games, with a lean 45-60min runtime (an experienced 2-player pair can wrap a game in 30mins), meaning that you can take the time to play a few hands and really let yourself get to grips with the different Gods’ varying abilities and strengths.

The theme of the game feels in some ways ideally suited to the mechanic at its core, while in other ways it feels a little superficial. The act of moving cards from your mortal coil down into the underworld feels beautifully thematic. That said, the Legends themselves inevitably end up as a weird mix of cards with often wildly different themes. While it would have been nigh on impossible to make every card meld together coherently, it feels like a missed opportunity that players’ Legends are entirely without narrative.

On the subject of the cards, it is clear that multiple artists have been responsible for the creation of the artwork. While it is generally all very pleasing, this does mean that there is a visible discrepancy between the different decks of cards which comprise the Agora. Some continue the wispy, desaturated feel from the box art, while others are in glorious technicolour. If it had been my design call, I think I’d have opted for something altogether different, styling the cards after Black and Red figureware akin to the 2015 video game Apotheon, which I found visually striking.

These criticisms notwithstanding, I would thoroughly recommend trying to source yourself a copy of this underrated little gem. It is unfortunate that there has not been a second edition of the game printed at time of writing, since it is getting harder and harder to find via online vendors or auctions for any kind of sensible money. All is not lost, though, and there is actually a fairly neat virtual module of the game available on Tabletop Simulator for PC. While it lacks the tactile appeal of the physical boardgame, it is a convenient way to try your hand at forging your own legends without risking COVID from one of the other demigods at your table…