Book Review: All Roads Lead to Rome

Do you think about the Roman Empire at least once a day? According to a Tiktok meme, most men do. Is this phenomenon an accident?

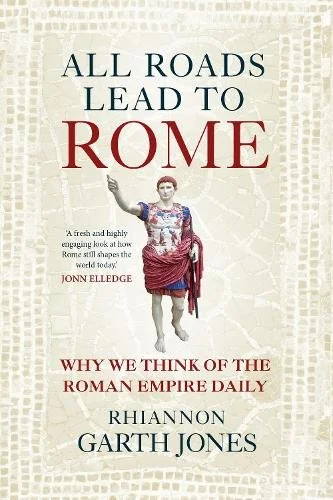

To answer this question (and many more you hadn’t even thought of asking yet) is Rhiannon Garth Jones’ stunning new book All Roads Lead to Rome. Spoiler alert - men (and women, because we’re humans living in modern society too,) really do think of ancient Rome daily, and it’s definitely not just an odd coincidental quirk. Our obsession is the result of millennia of people thinking about ancient Rome daily, and the proof is pretty much anywhere you care to look once you know what to look for. What does it mean to be Roman, or the inheritors of Rome? Several nations, empires and religions have grappled with this question, and the answers they come up with are stunning in their diversity. It’s not something that’s necessarily easy to spot, so thank goodness for Rhiannon Garth Jones, who guides us effortlessly across centuries and continents to explain how everything fits together.

The book is divided into three sections, each of which has a trilogy of deep dive case studies:

The Religion section discusses what most of us know as the Byzantine Empire, which is a title that would confuse its citizens who considered themselves to be very firmly Roman for centuries after most of us have been told the Roman empire fell. There is also a chapter on the Holy Roman Empire. The Danube river was a northern border for the Romans for nearly half a millennium, separating Roman civilisation from the barbarian tribes of Germania. How come, then, that a Frankish king whose capital city was Aachen, was crowned Emperor in Rome in 800 CE? And why were he and his successors so determined to emphasise their connections to Rome? Lastly, and depressingly relevant, comes the Russian concept of Moscow as the Third Rome, bastion of the Eastern/Russian Orthodox Church. It’s an old idea, but one that Vladimir Putin is happier reviving (and adapting.)

The Empire section similarly has an impressively wide geographic and temporal span; first up is the Ottoman empire who seized control of Constantinople in 1453 and whose Sultans subsequently used the title ‘Caesar of the Romans’ until 1922. Next is the British Empire, whose administration consisted almost entirely of Oxford-educated Classics graduates. They considered the Romans to be the superior ancient civilisation, and themselves superior for studying them, using Roman literature as a blueprint for pacifying and ‘civilising’ various peoples they very much deemed inferior. Finally, a chapter is dedicated to 20th century fascism in Italy and Germany- an ideology that is consciously named after a Roman symbol of power and authority.

The final section is devoted to Culture. We find a chapter about Arabia, which had formed a part of the Roman empire for centuries, and the early Islamic empires that flourished there who considered themselves staunch rivals of Rome, rather than successors. Next we see how the Founding Fathers created a New Roman Republic in the United States. The final chapter, which is probably my favourite, begins with the city of Rome itself, and the monuments and literature that speak of its own grapples with the great ancient civilisations that it interacted with during its rise to predominance, before ending in the ruins of Palmyra. It’s a perfect place to finish, bringing several threads from earlier chapters together; a diverse selection of peoples have a vested interest in Palmyra, whether in its preservation or destruction. The ghost city is not merely a pile of ruined buildings; it is a lightning rod for people who think about Rome every day, for better or worse. As this book has shown, an obsession with Rome - being Roman, echoing Rome, preserving Rome, surviving Rome, rivalling Rome - is one that has left a trail of human casualties. One of the latest is Khaled al-Asaad, the Syrian archaeologist who curated the site, and was executed by ISIS in the Palmyrene Roman Theatre. The collective global response to the destruction of Roman ruins and its protectors was immense, because Rome still holds a power over us, even in lands it didn’t know existed.

This is a book that keeps its audience in mind; you won’t need a history or politics degree to be able to keep up. The writing is fluid, accessible and engaging. One of the things I really enjoyed about the book (and will certainly influence my own writing in future) is not just that the author knows exactly how much context we need to understand some really knotty events and ideologies, but that she points us to further study. Usually, this is a dusty list of hefty scholarly tomes which enthusiastic readers without university library cards will find difficult to access. Here, Rhiannon Garth Jones points us towards podcast interviews with scholars, online articles, blog posts, and books that are widely available and affordable. Podcasts, Youtube videos and other forms of content are an excellent bridge between enthusiast and scholar, and we’re entering a Golden Age of engagement through their use. It’s fabulous to see this kind of public engagement promoted in a book. This is a book for everyone, and I suspect will be essential reading as the field of Classics gets dragged kicking and screaming into the 21st century. As part of the current trend of seeing the ancient world beyond the tightly guarded borders of Greece (Athens, really) and Rome at their peaks, this book provides a stark warning that seeing Rome through rose tinted glasses has far reaching consequences.

All Roads Lead to Rome is a book of dizzying scope, covering multiple empires and the men within them who couldn’t shake Rome; Charlemagne, Washington, Trump, Putin, Hitler, Mussolini, Mehmed II, to name a few. Their collective fixation has shaped our modern world that ensures that Rome is always, always at the forefront. It influences current events in significant ways, and this book is an excellent explanation of how thinking of Rome every day is irrevocably woven through the global headlines of the 2020s. There is no such thing as apolitical Classics.

I’ll let Rhiannon herself have the last word:

“Seeing this history clearly doesn’t change the world we live in but

perhaps understanding the choices people made before us helps us

with the decisions we will go on to make ourselves. Perhaps it gives us

new ways to see the world, new roads to take.”

“All Roads Lead to Rome” is published by Aurum and is available from May 22nd 2025.