If a tree falls in the North...

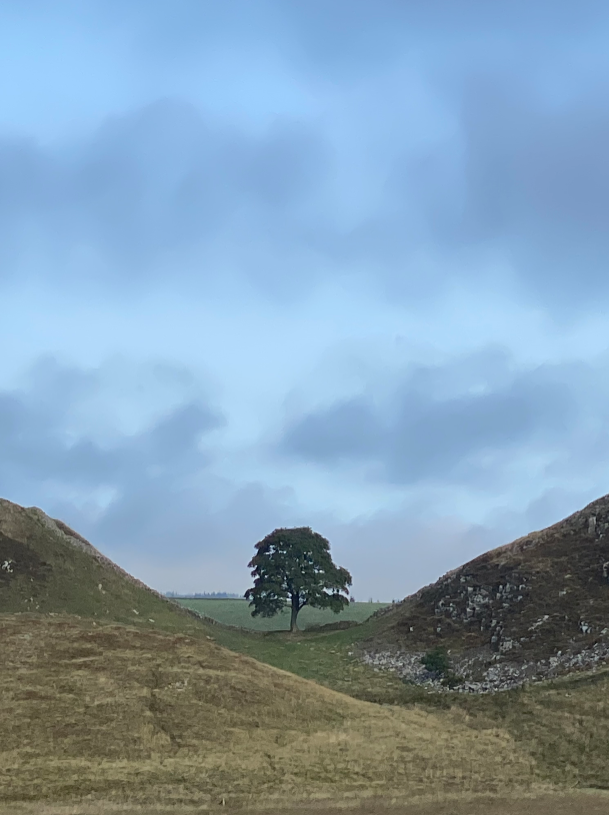

The iconic Sycamore Gap tree in Northumberland.

It was extremely sad to see the Sycamore Gap tree felled last week. It was an iconic part of the Northumbrian landscape, and indeed part of the Roman-British tourist landscape. When we think of the icons of Roman Britain, we have Vindolanda, the Roman Baths in Bath, Caerleon in Wales…but also this remarkable - albeit anachronistic - tree.

As most of us by now know, it had been in situ for three-hundred years, over that time drawing hundreds of thousands, possibly millions, of visitors.

Although there is no doubt that its destruction was an act of grotesque vandalism, and that it will emotionally and economically impact a huge number of people, the reaction to the felling of the tree was almost as disappointing as the act itself. People were very quick to jump in and condemn, proposing draconian punishment, and describing it as a cataclysmic act of cultural desecration.

The emotional impact will be felt keenly by those who had proposed to their partners there, had birthday and anniversary celebrations there, visited the tree with friends and relatives now gone, and created deep personal connections with the tree, which are now forever changed. People had key life moments under that tree.

And now a valuable mnemonic in the lives of those people has been removed.

Economically, it is disastrous because the icon of the Sycamore Gap, the image of the tree, draws tourists to a part of England which is often unexplored. In full disclosure, I lived in Northumberland between the ages of twelve and eighteen. In a disrupted childhood, it was the first place I really felt that I belonged, so my attachment to both the people and the place is visceral.

The loss of the tree will hit the economy of the county. The cultural violence of the act will reduce the number of people visiting Northumberland, which will reduce the number of people going to cafes, going to shops, going to garages, going to restaurants. There will be an economic consequence for local businesses.

I don’t want anyone to think that I do not think the act was abhorrent and awful.

The scale of the reaction on Twitter - and I know that Twitter is a platform that takes a megaphone to our worst, knee-jerk impulses - was disheartening.

People called for arcane, in some cases literally Classical, punishments for the offender. People used it as a barometer for a perceived decline in the respect for culture in the UK. There may be a degree of truth in the latter, but the former was simply an unhelpful overreaction.

A sixteen year old boy (and since, a sixty year old man) was arrested seemingly on suspicion of committing the deed, and as a teacher in a high school, I must again disclose a personal interest. What life events could possibly have led a sixteen year old to do this?

I reflected on my own time as a teenager in Northumberland. I was lucky because I fell in with a group of well-meaning geeks, interested in music and art and cinema and literature and history and nature and travel and the world. But even when I was at school, I knew that this group was not the majority of sixteen year old kids. We wish it were so, but it’s not.

Generally speaking, teenagers are interested in other teenagers; at a push, they are interested in music, video games, football and fashion. But the majority of teens do not have the same interests which my group of friends - and if you are reading this, then I expect you and your group of friends - had.

Some would say, “well, my son/daughter/nephew/granddaughter is interested in culture and they are sixteen”. That may be true, but they are not the majority of teenagers. They have had, in some way, access into the world of “culture” in a way that many are not fortunate enough to have.

In a place where there is so little for teenagers to do (this is not London or Manchester or Edinburgh) where will teenagers find youth initiatives and opportunities for self expression or development? To that we must add more than a decade of government cuts to these local resources. The usual expression of youth frustration and youth anger, when not given a chance to be diverted into art or music or sport, comes through violence or through other forms of crime, and cutting down the Sycamore is a crime.

We should not look at it through a lens prejudiced by our own affections, experiences and recollections. This is a crime which has come from some kind of frustration or boredom. I know some will say “well, I was bored as a teenager, but I had the gumption to get on and do things”. Yes, but like before, we have to remind ourselves that that is not the position of the majority of teenagers, and you are hearkening back to a world, ten, twenty, thirty, forty years ago. It doesn’t exist anymore.

Youth clubs, cinemas, libraries, sports fields, leisure centres, and other amenities which we were accustomed to when we grew up have been closed at a dizzying rate over the last decade. Add to that, musical instrument tuition in schools, drama groups, sports teams, after-school clubs: gone. Vibrant and exciting high streets? Forget it!

Again, you must remember that this is not comparing apples with apples. Teenagers today have a fraction of the outlets for their exuberance that we had.

So, for a moment, let’s imagine what leads a teenager to do this.

As a teacher for more than 15 years and an ex-social care worker, I feel I can speculate on the factors involved. These will include the remoteness of the location, and that being a child of technology and constant stimulation, as most teenagers today are, growing up in the sticks must be almost unbearably slow.

We also have to acknowledge something that older critics cannot level at this young person - teenagers are driven by popularity and an overwhelming desire for love, popularity to their minds being just a subgenre of love.

Throughout history, teenagers, in order to gain admiration - and therefore popularity and therefore love - have done rebellious things. For my dad’s generation, it was the teddy-boy rockers of the 1950s; for my siblings it was 1970s punk; for this generation, it is stunts and challenges for TikTok and social media platforms. These are the settings within which popularity can be accrued by bad or subversive behaviour. Every generation has its own version.

As a teacher, I have seen - as all teachers have - all sorts of terrible crazes based on bad behaviour in schools, on social media. TikTok is only the most recent platform.

We’ve seen kids remove the doors of bathrooms for admiration and popularity; we’ve seen them remove hand-dryers in bathrooms for admiration and popularity; we’ve seen the slap-a-teacher nonsense carried out for admiration and popularity.

They didn’t do these things because the act in itself was interesting or worthy; they did it because they thought it would look cool. For the geeks in school, looking cool is a more long-term endeavour to perform well, get good grades, go to university and get the hell away from other kids. Along the way there are short term goals of passing tests, finding friends and very often managing to keep a low profile and avoid the more unpleasant characters in their peer group. They may even have given up on being “cool” and had their self-esteem suffer for it.

None of this is new.

The expression is different and awful and wild and newsworthy, but none of the factors involved are new.

To bring the weight of the law down on a sixteen year old child, as many on Twitter quite violently recommended, would be inappropriate. Nobody is going to persuade me that all sixteen year olds are fully mature adults, in fact the prefrontal cortex (the part of the brain behind the forehead) is one of the last parts of the brain to finish maturing into your 20s. This area is specifically responsible for skills like planning, prioritising, and making good decisions.

It would be appropriate for the child to see the real consequences of their actions. To speak with people to whom the tree had a deep emotional connection, to speak to businesses who may have to make redundancies in the wake of declining tourist trade, to speak to conservationists, to be made to see the scale of the damage done - to the place where they live.

Because we should not assume that children do not have the capacity to understand emotions. Often they just require more guidance to see outside of their own feelings, which are front and centre at their age, dictating everything they do in a way we sometimes suffer from as adults in our weakest moments. Rebellion may involve acting against what is right, but rebels may also understand what they are kicking against, and in the case of children, rebellion is vaporised by the light of guilt. There is still a part of them that knows that one day they will have to be, and act like, an adult.

Locking the child up will turn them into a pariah, and from there into a criminal. You do not turn a delinquent into a citizen by treating them this way at a vulnerable age.

How, then, do we go forward in this morass of complex social and emotional gloop?

The child involved must have these conversations. There is no letting someone off the hook. The child knows they have done wrong. That’s why they did it. But if there were no admiration to be found in this act, if there was nothing to be gained from it, or anger to be taken out on it, they wouldn’t have done it.

There must be a consequence for the child. This is not a minor infringement of school rules, it is a crime which has deep consequences for a lot of people.

The family of this child likely needs some assistance. Even if the perpetrator has come from a well-off and culturally-attuned background, their parents were clearly unable to prevent this crime from happening. This is not judgement (full disclosure, I worked in Glasgow’s social work department for two years), but something has gone wrong in that home which requires a fix.

In the bigger picture, Northumberland needs more investment, more facilities, more things to do. You cannot be appalled by this act of vandalism whilst supporting a government which has stoked teenage frustration and boredom, and reduced the quality of life for teenagers, especially in the rural north.

This child emerged from a complex set of circumstances, not out of the ether. The forming of the child is not the child’s fault. They did not ask to be born, they did not get to choose where they lived, they didn’t get to choose their school, they didn’t get to choose the economic bracket they live in, they didn’t get to choose the cultural education they received, they didn’t get to choose the factors that formed them, especially early in their life. They have been formed - mostly - by the decisions of the adults around them, and those faceless adults in government.

Now that the child is on the cusp of becoming an adult, legally at least, we now say “this child is responsible”. It’s facile.

I agree, the child bears some responsibility, but that alone is not enough. We cannot metaphorically starve a dog and then wonder why it bites. We have a communal obligation to each other.

What has been done is awful and we know the consequences, but it’s so much more complicated than 280 characters on Twitter. We have become accustomed to passing judgments and opinions on all sorts of issues on the basis of such nugatory packages of information, and it’s not good enough. Good grief, a government was elected at the last ballot based on little more than three words: ‘get Brexit done’. It’s not good enough. Being informed matters.

Investment in the north of England, especially in child services, must increase. Economic opportunities for children in the north of England must increase. Transport connections between the north-east and more populous areas must increase. Social service investment in the north must increase - we cannot possibly hope to fix our society without greater investment in social services.

All of this, I regret to say, comes back to funding and money. If we simply punish the child, we are dealing with the symptoms, not the disease.

And the tree?

There have been suggestions of grafting the tree back onto its stump, of replanting a mature tree in its place. I don’t know if either is possible. Both would restore some sort of status quo (not the same, but similar). Historically, the area around the wall was heavily wooded and perhaps a greater benefit would come from reforesting the area.

I don’t know how I feel about any of these suggestions. A new forest is unlikely to provide an iconic visual which is of use to the local economy. All those individualised memories of the tree may be lost in the forest that replaces it. (Besides, one forest is unlikely to do a lot, environmentally speaking, against the opening of new oil fields, and a government too weak to phase out petrol cars.)

The Sycamore Gap tree situation is a symbol of a country which cannot decide what it wants to do. It wants to be environmentally friendly yet it cannot bring itself to do the things that would achieve that. It wants the regions outside London to be economically prosperous, but it refuses to pay for the things that would make it so. It wants its teenagers to behave in a certain way, yet it refuses to give them the resources to encourage that kind of behaviour.

I wish the tree were still in its place, as a sentry in that dip in the wall, looking north to Scotland. Its felling is a wretched story.

Because I also wish that teenagers (and anyone) in the north of England were more often in the minds of our cultural classes, who will howl the wall down for the loss of the tree, but have said nothing of any substance of the underinvestment in the area over the last ten years.

The Sycamore Gap tree.