The Antiquity to Alt-Right Pipeline

This post was ported from our original site on June 25th, 2024. At that point it had been viewed 12,199 times.

Introduction

The association between the ancient world and contemporary extremist political ideologies is well known among career classicists and amateur historians alike. For example, the etymology of ‘fascism’ is derived from fasces - bundled rods with protruding axe blades carried by lictors during the Roman Republic, signifying imperium, the power of the state.

Not only is the association widely-known, it has a long history: in 1922, Benito Mussolini’s government – considered by some to be the first government to be known as fascist – envisioned itself as an extension of the Roman Empire, while in 2015, outspoken white supremacist Richard Spencer encouraged white people to embrace their “forgotten” Roman identities. My aim is not to explain that there is a connection between Classical Antiquity and the Alt-Right, rather, I aim to understand how algorithms on social media sites such as Twitter[1] lead users who engage with content related to ancient history– particularly ancient Greco-Roman history– down an alt-right pipeline.

Inspired by my personal experience and Laura Bates’ investigation into misogynistic online content shared through Reddit and YouTube (outlined in her 2020 book Men Who Hate Women) I want to investigate what I call the “antiquity to alt-right pipeline” by recording the steps that led me there, critically assessing the content presented, and (hopefully) creating an effective way to respond to it as a Classicist, lover of ancient history, and chronically-online Twitter user.

Methodology

Twitter’s homepage, where users are delivered content, is called the “timeline” and offers up a variety of Tweets posted by accounts a user follows, along with suggested content selected by an algorithm based on a variety of factors. These factors include: if a user has previously liked a post from an account, if an account a particular user follows has commented on another post, if an account a user follows has reposted or “quote-Tweeted” a post, if an account a user follows follows another account, and if an account is subscribed to X Premium.[2]

Moreover, according to the X privacy policy, the social media platform only tracks users’ activity on the website and does not itself use third-party cookies to track activity on other platforms, making the Twitter experience an isolated one. The characteristics of Twitter’s algorithm, its open source code, and Elon Musk’s acquisition and subsequent commitment to “free speech”[3] makes it the ideal medium to explore an alt-right pipeline.

Twitter is also unique because of its popularity across demographics, particularly age and political affiliation. In this way, it stands out among other social media platforms such as Facebook, Truth Social, and Tiktok, all of which have less diverse user bases.

On April 5th, 2024 I opened a fresh browser linked to a new email and created a new Twitter account. My initial plan was to begin this new account by positioning myself as a person with general interests and a slight inclination for history. I would demonstrate this by typing in the term “ancient history” into the search bar and following the first accounts offered up to me.

When I began using my new Twitter account, however, I was met with something unexpected: the instruction that I select three “interests” from a range of options presented to me in order to personalize my feed. I feared doing this would be antithetical to my project, however, there was no option to skip this step. In alignment with my effort to be general yet hinting at an inclination toward history, I selected “entertainment,” “arts & culture,” and “travel.” I was then prompted to be more specific, choosing five from a larger pool of options related to my general interests. My selections were: “movies,” “art,” “historical fiction,” “language learning,” and “museums & institutions.” The final step in this process was to follow a minimum of one account.

The first account recommended was Elon Musk’s.

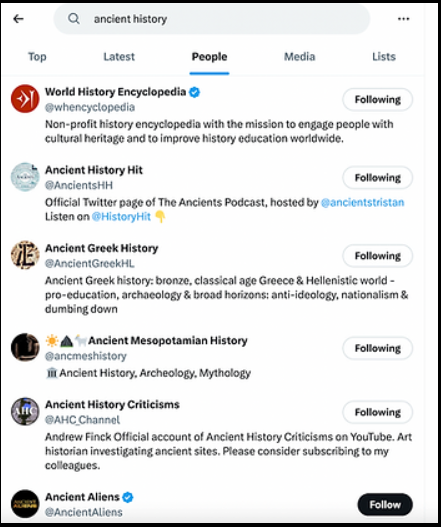

Assuming his is the first account recommended to every new user, I followed him. Already, I had to pivot as I had previously hoped to start from a completely blank slate. After arriving at the homepage, I entered “ancient history” into the search bar and followed the first five accounts recommended: World History Encyclopedia (@whencyclopedia), Ancient History Hit (@AncientsHH), Ancient Greek History (@AncientGreekHL), Ancient Mesopotamian History (@ancmeshistory), and Ancient History Criticisms (@AHC_Channel).

Screen capture by the author.

The goal of my investigation was to explore how engaging with ancient history-related content as a hobby-historian impacted my user experience on Twitter, with particular attention to the posts placed on my timeline and accounts recommended to me to follow. If I did end up being exposed to alt-right content, which was not a guarantee when I began my project, I wished to understand the connection between contemporary extremist political movements and Greco-Roman aesthetics as well as the rhetorical tactics creators use to radicalize their audience.

The methodology I developed for conducting this investigation was as follows:

I logged into Twitter every day and “liked” approximately the first 35 posts I saw that related to ancient history, in a very broad sense. Specifically, I “liked” posts which featured images of historic buildings, images of historic art and architecture, articles describing archaeological excavations, memes referencing history, and quotes from historical figures. I recorded every Tweet I “liked” in a notebook where I numbered it, recording the account handle, and including a brief description of the Tweet’s content. For some tweets, I bookmarked them, then took screen-captures to return to for later analysis.[4]

I only “liked” one post from one account per day, even if I saw multiple posts from the same account(s) on the timeline. This was to diversify the content I saw each day and ensure that I was not just going in circles, but exploring what the platform has to offer, thus using it as intended.

I always looked to the sidebar on the right of the Twitter webpage where it suggests “who to follow.” Regardless of what the accounts were being recommended to me, I followed all three that were displayed. If I had more time and wanted to follow more accounts, I clicked on the “see more” button which led me to a longer list of recommended accounts.

Investigation and Application of Methodology

Over the span of a month I “liked” approximately 600 Tweets, followed 60 accounts, and viewed thousands of posts. After “liking” approximately 65 Tweets, the account belonging to Andrew Tate (@cobratate) was at the top of my “who to follow” list.[5]

Adhering to my guidelines to follow accounts suggested by the algorithm, I clicked the “follow” button. This was the first time I was recommended content adjacent to alt-right and "manosphere" ideology. Prior to that, it was all history related. After “liking” approximately 100 Tweets, however, I saw that the accounts suggested to me were becoming increasingly political, and I was specifically being recommended accounts run by internet political commentators – as opposed to professional politicians or journalists. I cannot definitively call this observation evidence of being led down an alt-right pipeline, but it was interesting to note that those were the types of accounts suggested to me by the Twitter algorithm.

Despite this, no explicitly political content appeared on the timeline so I did not “like” it or engage with explicitly political accounts in any sort of way. The content appearing on the “timeline” was primarily related to ancient history and culture with a slight European leaning. That slight European leaning was evident from the conception of the investigation, however, because searching “ancient history” as a starting point yielded results primarily concerned with Greco-Roman history.

Although the nature of the specific posts being recommended remained the same, I began noticing that I was being recommended political accounts linked to right-wing extremists with regularity, particularly Catturd (@catturd2),[6] End Wokeness (@EndWokeness),[7] and Libs of TikTok (@libsoftiktok).[8] These accounts have high levels of engagement, post frequently, and subscribe to X Premium. All three of these factors make them more likely to be recommended to users, regardless of whether or not they relate to what users have previously engaged with. Therefore, I changed my method to following the first three to five accounts that do not explicitly reference politics or memes in their descriptions, which I continued for the duration of my experiment.

I was particularly surprised by the accounts recommended to me because not only were they representative of extreme political beliefs, but I was being recommended accounts related to Greco-Roman history and which also promoted equally extreme sentiments. I found this surprising because many of these accounts had fewer followers than accounts run by more established academics and hobby-historians, yet they were constantly recommended on my timeline.

For example, a Latin education account which uses Legos to teach Latin lessons, Legonium (@tutubuslatinus) has 34.4 thousand followers while Learn Latin (@latinedisce) has only 20.8 thousand. Similarly, Classical Studies Memes for Hellenistic Teens (@CSMFHT), an account that posts inoffensive jokes about the ancient world, has 497.8 thousand followers while Daily Roman Updates (@UpdatingOnRome), another meme account that often posts sexist and violent jokes, has 234 thousand followers. In both cases, the latter accounts were prominent on the “timeline” while the former accounts were not recommended even once.

Within the “accounts you may like” page, only the profile pictures, profile names, handles, and bio are visible. Users cannot see exactly what kind of content an account posts without clicking on the specific account. In assessing whether or not to follow an account, I did not first look at the specific content an account posted and made my judgments based on the four above factors. Deviating from the reliance on the Twitter algorithm, I shifted my methodology a little bit to reflect on how a typical user might behave. Using my new methodology I followed five new accounts, with an example of the information provided to me when I chose to follow them:

The Chivalry Guild (@ChivalryGuild) “Rediscovering things forgotten– Medieval thoughts for modern life – book out now!”

Tocharus (@Tocharus) “Working on a book. My Substack is how I’ll reach out directly and tell you it’s ready.”

Middle East & North Africa Visuals (@menavisualss) “The story of different lives in MENA – Alexandria University – sociology.”

Alexander’s Cartographer (@cartographer_s) “History, Geopolitics, and Art across Eurasia / writing a novel about Byzantine diplomacy / Essays and translations about Eurasian history.”

Academia Aesthetics (@AcademiaAesthe1) “Art & Aesthetics.”

Throughout my investigation, I realized that the little information provided about accounts has the potential to deeply impact user experience. Specifically, I think it can contribute to users engaging with prejudiced or offensive accounts without realizing it. A user, regularly encouraged to follow new accounts, is only provided a small amount of information[9] before they are prompted with the “follow” button. One may follow an account, becoming exposed to what that account posts and other accounts which it interacts with, with very little knowledge of any of those things.

This problem additionally occurs on the timeline. Posts which appear here are isolated from the accounts that post them. A user might see a post and “like” it, thus prompting the algorithm to recommend similar content, even if they dislike other content posted by that account.

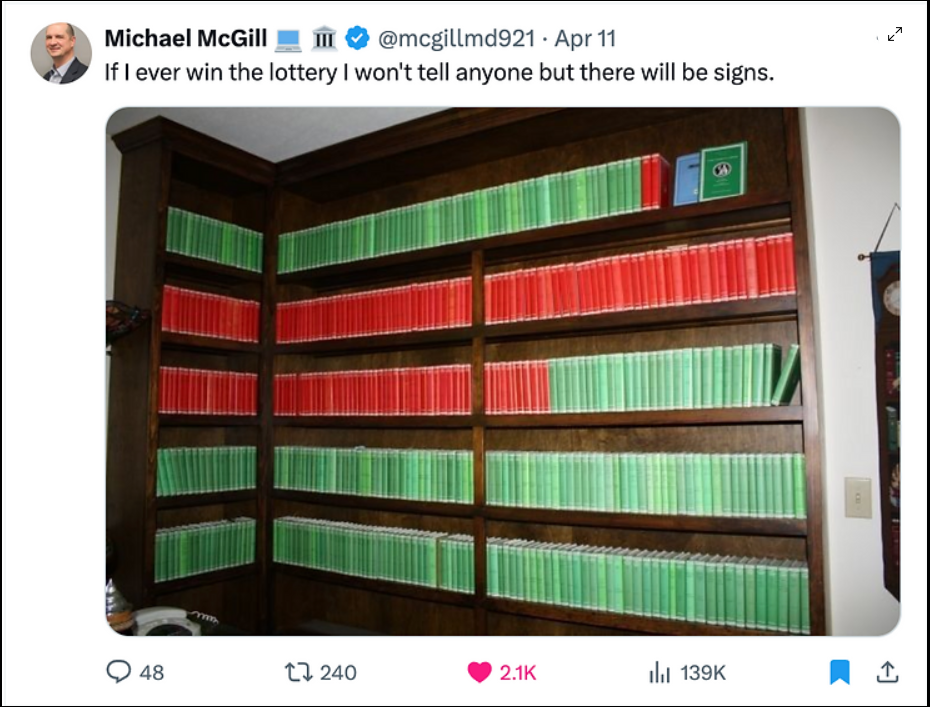

Screen capture by the author.

The above image is a screen-capture of how the post appeared on the timeline. Isolated, the post is relatable to many Classicists and bibliophiles. The caption, profile picture, nor username indicate the account which posted this has content that would be unrelated to books or harmful in any way. Nevertheless, this account in particular often posts sexist jokes about women being uninterested in Rome and unsupportive of their partner’s true aspirations, which are, evidently, to become a gladius-wielding legionnaire slashing apart Gauls on campaign with Julius Caesar.[10] Additionally, this account interacts with others which share the passion for Greco-Roman culture, albeit in a more chauvinistic manner. It is important to note that the majority of the accounts observed in my investigation are anonymous.

Observations and Analysis

Among the thousands of Tweets I viewed, I noticed that among the alt-right-leaning ones there were five prominent themes: violence as the ideal expression of masculinity; women contributing to the suppression of masculinity; objective beauty; threats to ‘white’ culture; and the duty to preserve one’s endangered culture.

“Men Would Rather Do This Than Go To Therapy”

Many of the accounts I came across were vocal about celebrating masculinity. What interested me in particular was the very narrow view that they celebrated. In alignment with #RomanEmpire and the British Museum post, they communicated the association between military conquest and masculinity.

These accounts, however, took the association even further, posting messages that argued military conquest and violence is a natural, healthy expression of masculinity. There were also a surprising quantity of messages telling men that they did not need to go to therapy, and that attending therapy is indicative of weakness. One account even went so far as to say that “violence is a critical component of men’s health” (@The_Hellenist).

The ultimate conclusion is that men need not go to therapy, they need to go to battle instead.

Any problems a man may be facing are attributed to his inability – or reluctance, in favor of therapy – to express his masculinity through violence. An outlier among these messages, although following a similar sentiment, argues that instead of going to therapy, men should learn Latin (@latinedisce). A photo of the Prima Porta Augustus accompanies the text, perhaps communicating that learning Latin will allow the reader to achieve military success or establish an empire.

“1 in 4 Men Are Happy”

Another popular theme explored by multiple accounts I interacted with over the duration of my investigation was that Rome is not for women. The sentiment manifests in a wide variety of memes expressing that women do not support their male partner’s interest in Rome, therefore, they do not support healthy, natural expressions of masculinity. Interests characterized as "female" are portrayed as trivial when compared to the greatness of male interests (@creation247). Finally, multiple posts share a sentiment that men would be better off without the women in their lives preventing them from pursuing their interests in Rome (@UpdatingOnRome, @projectethos5).

Screen captures by the author.

“The Bernini Pill”

Another way that accounts diagnose problems in society is by telling users that beauty is objective, however, objectively beautiful art has been hidden from view in favor of contemporary art that does not subscribe to standards of objective beauty.

Screen captures by the author.

As a result, contemporary society has been corrupted by the “modern art cult” (@Architectolder). The cure for modern art corruption, according to one account, is to take the “Bernini Pill”, to become Bernini-pilled. This language is directly drawing upon manosphere jargon referring to becoming red-pilled, which means to become radicalized. Finally, in both posts promoting the “Bernini Pill,” statues depicting rape scenes from Greco-Roman mythology are used to illustrate what objectively beautiful art should look like. The choice of statues additionally suggests the idea that expressions of masculinity through violence are natural.

“This is What We Are Up Against”

Multiple accounts expressed a pessimistic outlook on contemporary society, comparing our modern epoch to the fall of the Western Roman Empire. A popular argument in these accounts is that the Western Roman Empire collapsed because of unprotected borders, allowing violent barbarians into the city who ruined what the Romans had built.

Screen capture by the author.

A post from @UpdatingOnRome (below) suggests that the Edict of Caracalla, granting citizenship to freeborn men in the Empire in 212 CE, resulted in an influx of barbarians coming to Rome, despoiling it. This xenophobic narrative is often used to argue that our own contemporary society is collapsing due to multiculturalism. @latinedisce suggests that contemporary historians are revisionist to suggest that Rome in the early imperial period was diverse and its residents, even the native Italians, had dark skin. The common theme among these posts is that they perpetuate a moral panic that ‘white’ heritage is being erased and modern society is failing as a result – shouldn’t we have learned from the sack of Rome in 476CE?

Screen captures by the author.

“We Must Retvrn”

In response to problems suggested by these posts, the proposed solution is to pursue the return of Greco-Roman values – and with them, pride in one’s ‘white’ heritage – in order to combat threats to history, culture, masculinity, and identity.

Rarely do accounts provide specific instructions on how to accomplish this outside of Twitter, or even what it specifically means.

More often, photos of great monuments or heroic statues are paired with affirmations encouraging viewers to “become the greatest man your bloodline has ever seen” or simply to “retvrn”[11] to what has been lost.

Screen captures by the author.

Why Does the Alt-Right Love Antiquity So Much?

While portraying the ancient Greco-Roman world as monolithic is an inaccurate reflection of history, it is nevertheless vital to the construction of alt-right mythology. Subscribers to this mythology often hail the Classics discipline as an academic branch protecting it. Therefore, transitions in Classics toward more equitable pedagogy and away from white-supremacist ideologies are frowned upon.

In 2019, James Delingpole,[12] published an article to the news site Breitbart[13] titled O Tempora, O Mores! Social justice is killing Classics in which he wrote: “If there was one area of learning guaranteed never to be hijacked by the forces of ignorance, political correctness, identity politics, social justice and dumbing down, you might have thought, it would be Classics”.

The alt-right only celebrates the cultures of the ancient world in their capacity to model, to justify, and to explain their fascist ideology.

Those who claim they want to return to the Greco-Roman past only ever imagine themselves as imperatores. Perhaps that’s because explaining the realities of injustice in the Roman past would make the idea of returning to it much less attractive.

The Richard Spencer-types never imagine themselves as part of the ancient population who was enslaved, the population made up of women, or living in a province violently colonized by the Romans. To figures like Spencer or Delingpole, however, historical accuracy is less important than constructing a seductive narrative with extensive lore in order to establish historical precedent.

Similarly, the nature of radicalizing content that celebrates the ancient Greco-Roman world, as it appears on Twitter, has much in common with incel and alt-right ideologies, specifically sharing anti-feminist views and rhetoric that Greco-Roman culture has been censored, leading to a bastardization of western society.

What makes content on Twitter more dangerous is the fact that it appears to users who do not seek it out. The manifestation of radicalizing content on the timeline encourages its normalization and champions the insidious ways violently prejudiced rhetoric seeps into popular culture.

Tragic? Comic? (Image created by the author.)

Footnotes

[1] In 2023, Twitter was renamed X by CEO Elon Musk. I maintain its original name because that is how it is still known in the vernacular.

[2] X Premium is a subscription-based service offered by X as of December, 2022.

[3] When Elon Musk acquired Twitter in April, 2022, he promised to be committed to “free speech” on the platform. What he meant by that, however, has been unclear despite him Tweeting a clarifying statement later in April, 2022: “By ‘free speech’, I simply mean that which matches the law [of the United States]. I am against censorship that goes far beyond the law”. Thus far, his commitment to “free speech” has manifested in reinstating accounts of controversial figures previously banned from the platform such as Donald Trump and making significant cuts to the content moderation team.

[4] All Tweets in this paper are ones I came across over the duration of my investigation from April 5th, 2024 to May 5th, 2024.

[5] Andrew Tate (@cobratate) is a popular men’s rights activist and member of the “redpill” community who has gained a significant online following posting content relating to masculinity. He is currently being investigated in Romania, where he lives, for his involvement in sex trafficing and rape charges. A 2024 article published by the Anti Defamation League names Tate as a driving force behind the mainstreaming of online misogyny.

[6] Catturd (@catturd2) is the online pseudonym of American political internet figure Phillip Buchanan. Active since 2018, Buchanan has garnered a reputation for promoting conspiracy theories, disinformation, and crude humor. A 2023 investigation by Media Matters for America found that Buchanan was manipulating the Twitter algorithm to drive engagement. Yes, it is pronounced “cat turd.”

[7] End Wokeness (@EndWokeness) is an anonymous account on Twitter active since 2022. The account bio reads: “Fighting, exposing, and mocking wokeness.”

[8] Libs of TikTok (@libsoftiktok) is an account owned by Chaya Raichik, a former real-estate agent who posts anti-LGBTQ+ content online. In 2024 she assumed a position on the Oklahoma Public Library Advisory Board despite having no former political career. She has been active since 2020.

[9] See Michael McGill @mcgillmd921. “If I won the lottery I won’t tell anyone but there will be signs.” Twitter, April 11, 2024.

[10] Contents and themes of posts as well as specific examples from this particular user will be discussed in a later section.

[11] The ‘v’ in ‘retvrn’ is likely meant to replicate Roman inscriptions where the letter ‘u’ appears as ‘v.’

[12] James Delingpole is a self-described libertarian conservative and climate-change denier from Britain.

[13] Founded in 2007 by American political commentator Andrew Bretibart. Breitbart is a conservative news outlet notorious for promoting misinformation and conspiracy theories.

About the Author

Tallulah Trezevant studies Classics and Medieval Studies at University of Illinois as an undergraduate. Her research interests include depictions of slavery in Roman Comedy, online political receptions of the ancient world, and understanding the impact of Roman imperial expansion through archaeology and historiography. Tallulah is currently writing her undergraduate thesis examining the uses of ancient aesthetics to propagate alt-right ideologies online.