Ancient Athletics Part Seven: Five is a Magic Number

The three most important disciplines of the pentathlon: diskus, javelin and jumping weights in background. Tondo from an Attic red-figured kylix, ca. 490 BC. From Vulci.

Introduced: 708 BCE (adult) with a single youth event in 628 BCE

Pentathlon translates as ‘five competitions.’ A good pentathlete was good at two or three of the events, and an exceptional pentathlete excelled at all five. That wasn’t easy, as the skillset was diverse and mastering five disciplines required extensive training on top of talent. The pentathlon was slightly different to our modern iteration, and (it’s thought that) the events ran as follows:

Discus

Long Jump

Javelin

Stadion sprint

Wrestling

For each jump and throw, the athletes were allowed three attempts and their best result was recorded. One of the problems historians face with the pentathlon is that nobody in antiquity ever bothered to write down how scoring worked. Some scholars think that the first person to win three events won, and that if that happened before the sprint or wrestling, they just got cancelled. There is one inscription that supports this. Some scholars believe that athletes got knocked out as events passed if they didn’t win anything, meaning that only athletes who had won at least one event got to progress to the stadion. Logistics wise, this makes sense; if every competitor reached the wrestling round, that portion of the pentathlon would be rather lengthy. Others suggest the lowest scoring athletes were eliminated in each round, and that the wrestling determined which of the qualifying athletes would take home the wreath.

Another theory is that only people who had won two events could progress to the wrestling, because a winner apparently had to win three events. This doesn’t explain what would happen if four separate athletes won the first four events, so perhaps only the winners of the discus, long jump and javelin advanced to the sprint? All we have is conjecture, so scoring will have to remain a bit of a mystery. So are statistics; measurements of jumps and throws were recorded on the day only and not kept for posterity, so we have no idea about average or winning distances, or who was the all-time best at each event.

We’ve already discussed how the stadion sprint and wrestling worked, so let’s investigate the others:

Rhythm was important to the discus, javelin and long jump, so the following events were all accompanied by musicians.

Discus

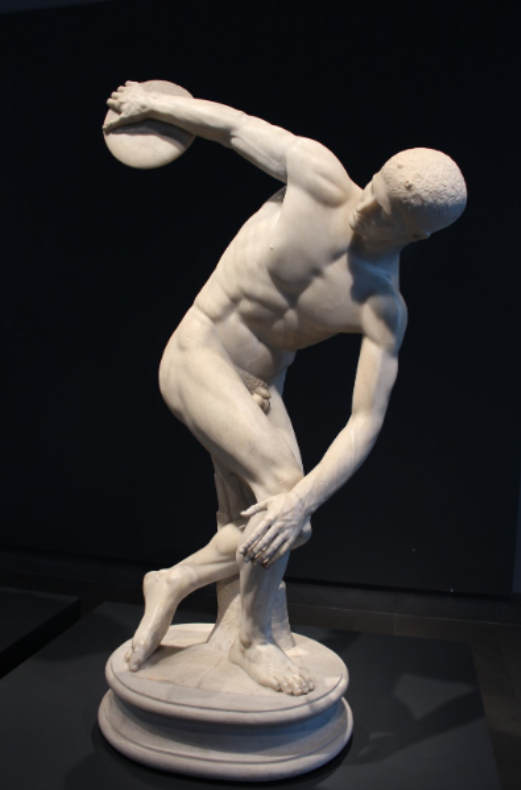

Each Greek athletic festival had their own ideas about what a standard discus should be. Some are wider, some are particularly heavier than average, and they could be made of stone or cast metal. Pausanias reckons that at Olympia, there was a set of three bronze discuses that were kept in the Treasury of Sikyon. They’d be brought out and each athlete would throw the three discuses and their longest distance recorded. In this way, nobody could sneak in a lighter discus. We have no idea whether athletes stood still to throw or span around like modern discus throwers, but at the very least athletes twisted back before flinging their arm forwards in an arc to throw. You can see the movement in Myron’s famous statue of a discus thrower, which we know from copies of the original.

Discobulus. Roman copy of the Greek original. Palazzo Massimo. Photo: author’s own

Javelin

Like the discus, athletes threw three javelins along the stadium and their best effort was measured. The javelin was wooden, and about the same height as the athletes. Scholars aren’t sure if the javelins were thrown from a standing position, or if the pentathletes could make a short run up to the stone starting line. What we do know is that the javelin was launched using a long leather strap. The strap was folded in half, and wrapped around the centre of the javelin shaft, leaving the middle of the strap as a U shaped loop. The athlete placed his fingers through the loop and threw the javelin forwards, keeping a tight hold on the strap. As the strap quickly unwound from the javelin, it caused the javelin shaft to spin in the air (like a bullet from a rifled gun) which made the javelin more stable and accurate, allowing for greater distances. Accuracy was vital, because nobody wanted to kill a spectator. Estimated winning distances are around 300 feet, only 23.1 feet less than the current world record.

Long Jump

Again, nobody is 100% if pentathletes jumped from standing or were allowed a run up. But we’re sure that athletes held weights called halteres in their hands during the jump, and a little experimental archaeology can help clear up the confusion. Modern athletes (who run up to the jumping line) find that the weights reduce the length of their jump. But, if jumping from a standing position with both feet together, weights have been found to increase the distance of a jump. No ancient athlete would want to hinder themselves, so it is likely that the long jump was taken from a standing position. Athletes stood at a line on the edge of the softened skamma, swung their hand weights (weighing around 1.5-2kg) back, then forwards, with the momentum of the stones helping to launch their bodies forwards. The skamma was around 50-55 modern feet long. The current modern long jump record doesn’t exceed 30 feet, but in antiquity we hear of athletes clearing the skamma. Because of this, scholars suspect that best attempt of three jumps was not recorded, but that the second and third jumps were launched from the landing spot of the previous jump and that the total distance was recorded.