Ancient Athletics Part Six: Kicking and Punching

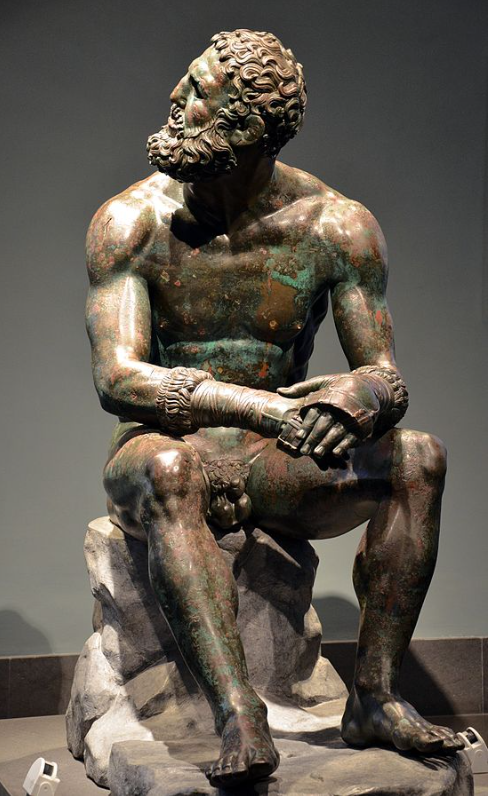

Boxer of Quirinal, Greek Hellenistic bronze sculpture of a sitting nude boxer at rest, 100-50 BC, Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome

Combat athletes were instantly recognisable, not just because of their cauliflower ears and misshapen noses, but because their training gave them very different physiques to the track stars. They took training seriously, with diets of carbs and red meat and exercises designed to bulk them out. Speed wasn’t always the best tactic, not when you could be simply too massive to move. Modern combat events have weight classes, but there was no such thing in ancient athletics. Nobody wanted to be the scrawny wimp going up against a man mountain, because nobody expected the wimp to win. So, combat athletes usually boasted barrel chests and thick thighs.

All combat events hinged on strength and endurance. They took place in the stadium, in an area called the skamma. It was created by breaking up an area of the running track with picks and softening the dirt there with water, which helped absorb the impact of throws and falls. There are referees to ensure that combatants stay in the designated area during the events, and to closely monitor for illegal manoeuvres. Because there were preliminary rounds in Elis before the festival began, spectators would be watching the the crème de la crème of the combat athletes competing, and could expect to enjoy what we might call the quarters, semis and grand finals. Competitors were drawn by lot, until the last pair standing reached the final. That meant that the finalists had to fight several times, all in the space of a single afternoon. The finals were therefore not as explosive as the earlier rounds, and it was a wise athlete who didn't exhaust himself too soon. To prepare for a fight, the athletes oiled their skin, then covered themselves in dust (as being too slippery might give an unfair advantage.)

Wrestling (pálē - πάλη)

Introduced: 708 BCE (adult) 632 BCE (youth)

A wrestling match was won by the first competitor to score three points. Points could be gained in the following manner:

Causing your opponent to touch the dirt with his back, hip or shoulder

Causing your opponent to yield

Causing your opponent to leave the skamma.

Wrestling was all about holds, grapples and throws, so no punches or kicks were allowed. You couldn’t bite either, or try to poke their eyes out, or yank on their genitals. Try it, and the referee was allowed to whip you until you desisted. As such, it was all a very gentlemanly affair. For instance, a wrestler might try to choke the life out of his opponent by squeezing his neck, or he could snap a limb, or break his opponent’s fingers. All of these were legitimate approaches. After each point, the wrestlers could have a quick breather before beginning again, which is a luxury boxers were not afforded.

Boxing (pygmachia - πυγμαχία)

Introduced: 688 BCE (adult) 616 BCE (youth)

Philostratus says that the Spartans invented boxing, but not in a form that we would necessarily approve of.

Ancient boxers didn’t fight their bouts in rounds with a short break for a drink and a pep talk from their trainer. Fights were continuous and lasted as long as they needed to. There were no rounds, no chances for a rest. The event could only be won if an athlete tapped out, was knocked unconscious, or died. Bearing in mind that the athletes wore nothing to protect their heads, this was a distinct possibility.

Neither did they use large, padded gloves. Ancient boxers wound 4 metres of leather softened with oil called himantes around each hand and wrist, leaving the fingers free. This protects the hands of the wearer but certainly not the skin of the opponent. Himantes caused such stinging cuts that they were nicknamed ‘ants.’ Any type of blow from the hand was acceptable apart from gouging.

Certain boxers boasted that their faces were still unmarred because of their great skill. One, named Meloncomas of Caria, remained undefeated for his entire career without ever throwing or receiving a punch, relying on nimble footwork and the ability to keep his guard up for up to two days at a time.

Otherwise, veteran boxers would have been instantly recognisable from their cauliflower ears, broken noses and numerous scars, perhaps with a few teeth knocked out for good measure. Eurydamas of Cyrene lost every single one of his teeth in a single fight. Apparently an aristocratic Roman entered the Olympic Games and when he got home was disowned by his family, losing his inheritance. He was so badly disfigured during his bout his family didn’t recognise him.

There is a memorial at Olympia from the 1st century AD to a boxer known as the Camel of Alexandria. It reads ‘He prayed to Zeus, “Give me victory or give me death!” And here in Olympia he died, boxing in the Stadium at the age of 35. Farewell!” ‘

It appears from ancient depictions of boxing that the head was the primary, or even sole legitimate target, but blows to the body were not unheard of. Pausanias recounts the story of Damoxenos of Syracuse and Creugas of Epidamnus, who were competing in the boxing final at the Nemean Games. The bout seemed never ending, so the two made an agreement to end the match with a knockout. In turn, they would land an undefended blow until one of them could no longer stand. Creugas landed a blow to the head, Damoxenos didn’t yield. Damoxenos, on his turn, didn’t aim for the head. He outstretched his fingers, jabbed them into Creugas’ side beneath the ribs, grabbed onto his internal organs and yanked as hard as he could, pulling them out of Creugas’ torso. Creugas died instantly.

But Damoxenos didn’t win - his open hand move was judged a foul, and Pausanias suggests that each of his fingers was counted as a separate blow. The bargain had been to strike one blow each. The corpse of Creugas was declared the victor, and a wreath placed on its head.

Detail of Boxer of Quirinal showing himantes. Palazzo Massimo. Photo: Author’s own.

Pankration (παγκράτιον)

Introduced: 648 BCE (adult) 200 BCE (youth)

If boxing sounds violent, you ain’t seen nothing yet!

Pankration comes from ‘pan’ meaning ‘all’ (think Panhellenic, all of the Greek world) and kratos meaning ‘power’ (think democracy: demos meaning people + kratos = power of the people.) So ‘pankration’ literally means ‘all forms of strength/power.’ Nothing in the modern iteration of the Games is quite as brutal and terrifying as pankration. It’s more than just a wrestling/boxing mash up, it’s an all-out extravaganza of violence. There were only two rules:

No biting

No eye-gouging

So unlike wrestling, attempting to tear off your opponents’ testicles was a legitimate tactic. So was hair pulling, so it made sense to shave off hair from…pretty much everywhere. Grapples, holds, throws, kicks, punches, and everything in between was all considered fair game. To a modern eye, pankration is utterly savage. To the ancient audience it was a highlight of the games and a masterful display of skill, strength and determination.

Like boxing, there were no rounds or points. Yielding, unconsciousness or death were the only way a match ended. With such freedom came a host of fighting styles within the event and the random lots must have made bouts between famous pankratiasts with differing techniques a must-see event.

Determination and the endurance of pain were seen as honourable in the eyes of spectators and, as we often do now, crowds would sometimes cheer for underdogs if they showed fortitude. Pankration wasn’t just a competition of who could inflict the most pain, but who could take the most pain.

And take pain they did, for pankration caused broken bones, dislocated joints, and massive bruising both internal and external. Despite only having two rules, pankration wasn’t a free-for-all. There were different methods and tactics to choose from, and each athlete had their own style. It meant that no bout was the same. Even if, to us, pankration seems like an ultra-violent brawl, there was an immense amount of skill involved and talented pankratiasts were highly regarded.

There have been several attempts to get a watered down version of pankration introduced as an event in the modern Olympics in recent years, hopefully with fewer broken bones and dislocated limbs…