How I fell in love with the classical world

Jacky Boland

Feb 25, 2022

4 min read

ATTENTION! There’s been a robbery.

I discovered the world of Greek mythology and subsequently the classics during lockdown 2020, along with a renewed love for reading and banana bread. Until then, it hadn’t even been a blip on my radar. At no point had it entered my sphere of awareness. Sure, my brain had soaked up the names of a few Gods in passing (“Yeah, Zeus, Greek Thor innit”) and I knew who Hercules was (according to Disney) but other than that, just some planets and bad movies.

I genuinely only realised why Hermes the courier is called Hermes last year.

And now I can’t stop asking why? How had I missed this huge, insane and rich part of history? Why didn’t I know these stories already? I feel robbed of years of passion and interest in what I’m only now scratching the surface of.

And what sparked my obsession (because, oh boy, it is an obsession), you ask? Hades, the award-winning dungeon crawler video game from Supergiant Games—my favourite game of all time and an actual piece of art. Around the same time, I picked up the book The Song Of Achilles and the web comic Lore Olympus and really, I had no hope, did I?

Hades follows Zagreus, Prince of the Underworld, as he attempts to escape the realm of his father, Hades. It honours a wealth of myths and characters beautifully while expanding on them and adding a little extra… spice (I would die for Thanatos and Zagreus). Wanting to know as much as possible about these hilarious, rich and alive characters and where they came from springboarded me into researching as much as possible.

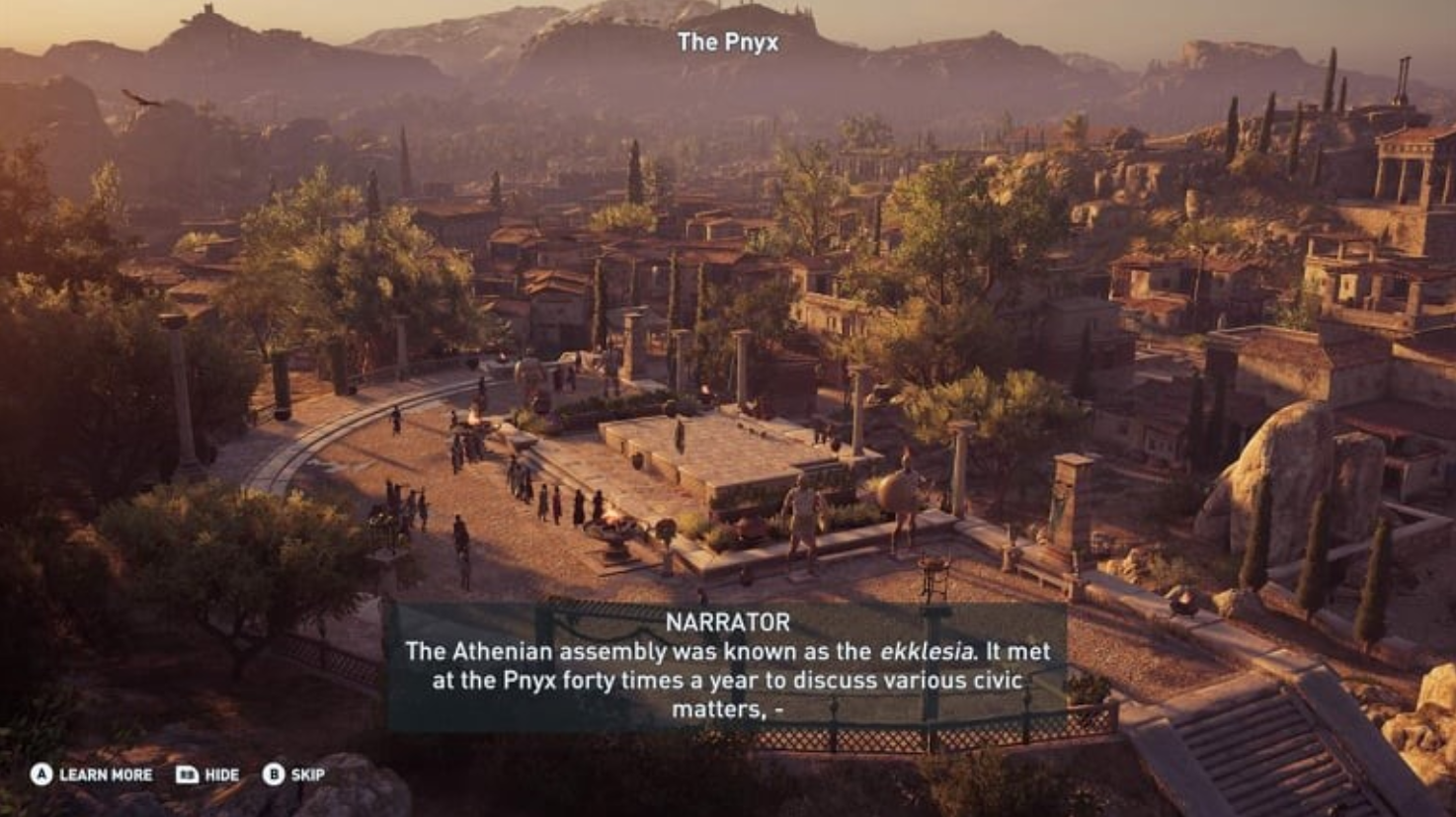

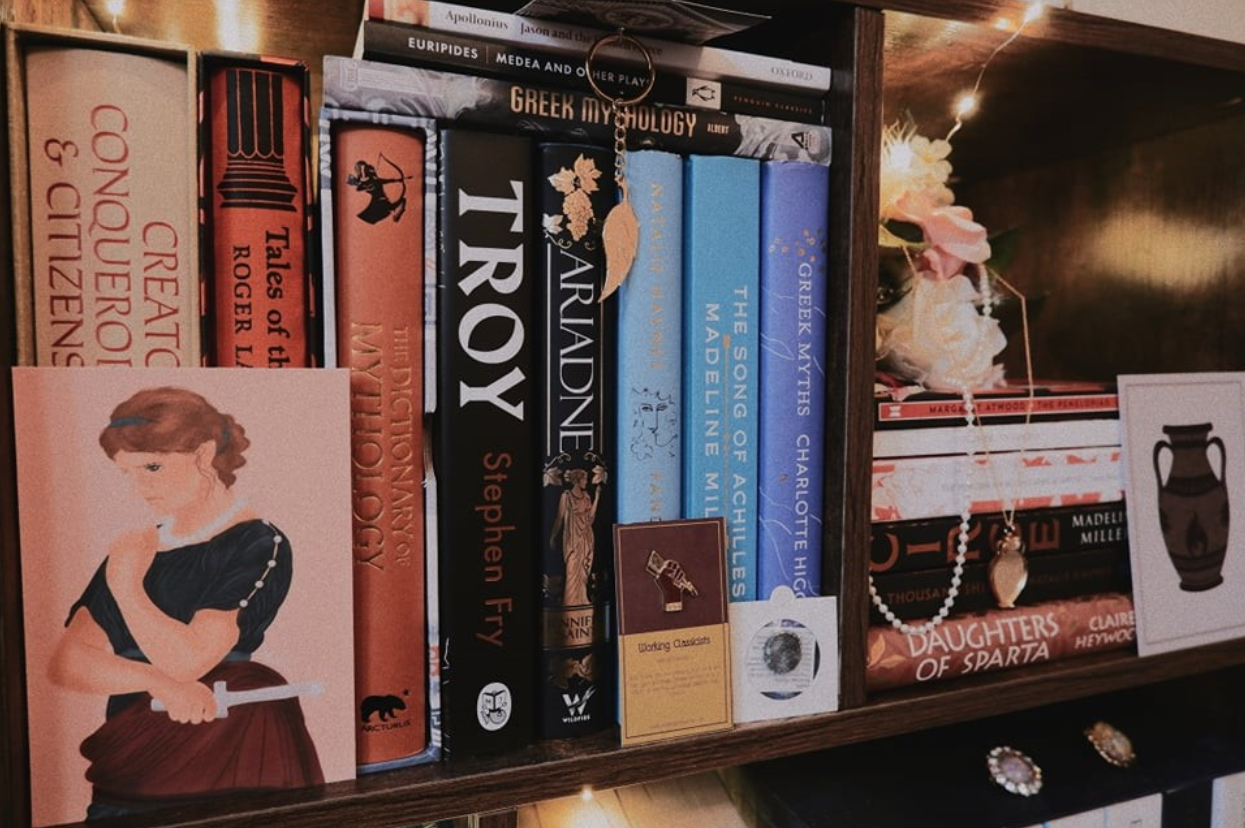

Madeline Miller led to Natalie Haynes led to Roger Lancelyn Green led to Euripides and on and on—cut to now and my rapidly diminishing shelf space. Not to mention the games Immortals Fenyx Rising, which is criminally underrated by the way, and the Assassin’s Creed Discovery Tour modes which have taught me more than any history classes ever have.

Greek myth is having a bit of a moment, especially women in antiquity, demonstrated by the range of fantastic books reimagining mythology through women’s voices; A Thousand Ships by Natalie Haynes, Ariadne by Jennifer Saint, Circe by Madeline Miller and Daughters of Sparta by Claire Heywood, to name a few.

These are my text books. The games are my classroom. When you ask experts and academics what brought them to the classical world, it’s usually a particular story book or movie from their childhood. We’re looking at a new wave of catalysts of interest in the classics and proof that the appetite for the subject is as ravenous as ever.

The way these myths are told and received now tells us as much about our society as the vases and frescos tell us about the ancient world. As Charlotte Higgins writes in her book Greek Myths: A New Retelling: “These stories of far away and long ago can be used by us as Euripides once used them—as lenses through which to see our own times more clearly.”

A highlight of my journey of discovery and personal favourite is Medea. First stumbled across in Tales of the Greek Heroes recounting of Jason and the Golden Fleece, I thought ‘Medea the Witch-Maiden’ sounded like my kind of woman. Especially since she’s the only reason Jason gets anything done at all! I’ll skirt past the bit where she chops her brother into little pieces and murders her children…

But even that! Rarely do you see women in mythology be so central to the story, with agency, as complicated and flawed and nuanced as the men. And with so many altering accounts and versions that is par for the course with myth, some say she didn’t kill her brother or her children at all. How we interpret these stories, when we wonder what they might really mean, what might we learn about ourselves?

The very nature of ‘myth’ is to be shared and retold and made your own, as was the case in the ancient times when they were first uttered. The words cascade through generations passed over hearths, sung alongside the plucking strings of a lyre, etched into stone and papyrus and even the stars themselves. The classics have always belonged to everyone, not to be gatekept by a few.

Now we’re in a situation where classical studies has largely become a staple of private education, an entire world of references and shared knowledge that the average person isn’t privy to. Where a working class education only allows you to study what makes you employable, a good statistic for their record, the privileged are able to study what interests and enriches them.

In the same way that the exclusion and mistreatment of women in antiquity has been a detriment to the classics that is now being reclaimed, so too is only allowing access to a privileged, limited few.

Classical reception in popular media isn’t just fun, it’s imperative. How the subject matter is used in film, books or games shouldn’t be scoffed at or ridiculed for “inaccuracy” when they’re inspiring a new cohort of classicists who wouldn’t otherwise have had the opportunity.

Storytelling, in all of its forms, is the oldest and best method of teaching since you don’t realise you’re even learning anything at all, and if these stories have survived thousands of years so far, perhaps it’s because they hold something vital that everyone needs to hear.

Jacqueline Munro is a writer, reading fanatic and classics enthusiast from West Yorkshire, living in Scotland.