Taking a Name

Cora Beth Fraser

Feb 18, 2022

4 min read

Most classicists have at some point come across the tombstone of Regina - maybe in source books or documentaries, or on a visit to the British Museum or the Great North Museum which display replicas, or in one of the numerous academic articles that have been written about it. It always gives me a jolt when I see Regina mentioned, like an unexpected encounter with a member of my family.

Found in my home town of South Shields, just south of Hadrian’s Wall, the tombstone was set up on the outskirts of Arbeia Roman Fort in memory of a woman called Regina, by her husband. She was British, from the South of England, and was married to Barates, a Syrian from Palmyra, when she died at the age of thirty. She had once been a slave.

Photo by Cora Beth Fraser.

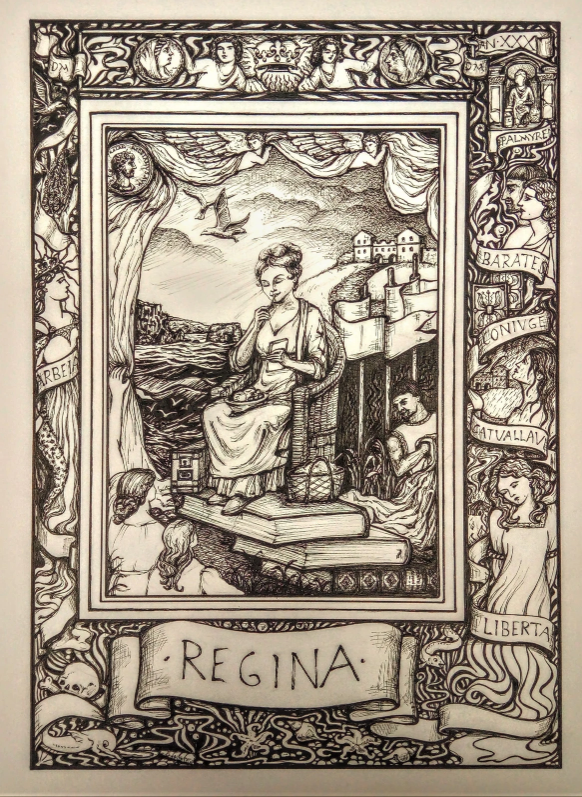

Her tombstone shows a seated figure, now missing the face. She’s surrounded by objects signifying virtue and status: a basket of wool, a spindle, a casket maybe for money or jewels. The wicker of her chair is just visible behind her. From the inscription (in Latin) we find out her name and nationality, her status as freedwoman and wife, and her age; and from the lower inscription, in Palmyrene Arabic, we see a personal message:

Regina, freedwoman of Barates, alas.

Regina is used in the academic world as evidence of all sorts of things: movement of people around the empire, multicultural settlements, multiple languages and so on. But to me she was a childhood friend and teacher.

I grew up working class. That means very different things to different people. To me, it meant a roof over my head, a loving family and a careful but creative childhood. The charity shops were too expensive for us, so we used to make our own clothes. My parents saved up for my school shoes over months, and I treated them like glass. The heating went on only after all other measures had been exhausted, and was seen as a sign of weakness. We had no car, no computer, no foreign holidays and no restaurant meals.

Our circumstances weren’t upsetting, though; the family hadn’t fallen on hard times. On the contrary, my parents had grown up with less, and my grandparents had been poorer still. Most of my friends were in similar situations or worse, with many parents losing their jobs when the pits closed down. I had one middle-class friend whose bathroom had two sinks and a bidet, and I grew up believing that money made you cleaner but not happier.

Like many other careful families, when the weather was cold we went out to places where we could stay warm without spending money: libraries, churches, free museums. My dad mined the Reference Library for instructions on anything and everything; my mother was a voracious reader who took out a stack of books every week; and I worked my way steadily through the children’s library until I demonstrated at the age of 10 that I’d read every single book, so that they would give me an adult library card. That card was my proudest possession for years.

I can’t remember a time before I met Regina. Her tombstone, and the rest of the free Fort museum, was part of my childhood. My parents, too, grew up with her, and my grandmother used to visit the Roman Remains before a museum was built on the site.

I didn’t know Latin, didn’t even know there was such a thing as Latin literature when I was a child; but I could always read Regina’s inscription. It had names and numerals, so I suppose it wasn’t difficult to match up the English translation with the Latin words. I don’t remember it as a conscious process, or even as an awareness of a different language; it was just one of the things I picked up.

In many respects my early acquaintance with Regina shaped my later encounters with literary Latin. I never saw Latin as something that was by or for the elite: clearly it was used by everyone, even British ex-slaves in a chilly little seaside town, and could be read by everyone, even small girls visiting a museum because it was warm and free. I never saw Latin as a privileged language, because it was paired with Palmyrene when I first encountered it. I never saw Latin as the property of men, either, because in my little corner of the world it wasn’t.

I encountered all of those attitudes later on, in various forms, when I became a student of Classics, and I’m still coming across them even today. They have serious implications for our discipline, in that they act as a barrier to people who don’t fit the stereotypical ‘classicist’ mould.

This bothers me; but I can find amusement in it too, thanks to Regina. A British woman, enslaved, freed, and finally married to a Syrian man at the edge of empire, she had good reason to see Latin as something that did not belong to her. And yet her inscription, in Latin, defiantly sets out her non-Roman, non-elite status. Her name, too, means Queen. Maybe the name was given to her as a slave, in a spirit of irony; maybe it was a nickname she acquired for her mannerisms; or maybe she chose it herself. Whatever the case, she sits on her wicker chair like a queen on her throne, proclaiming her name to all those who pass, in a language that she took for herself.

Regina is the reason why I’m happy to call myself a classicist. The term ‘Classics’ has a lot of elitist baggage: it can exclude and offend, and it baffles most ordinary people. It was not created for people who only went into a museum to warm their hands on the radiator. But like Regina, ex-slave and self-proclaimed provincial Queen, I find some satisfaction in taking a name that should not be mine and making it my own.

This illustration is my thanks to Regina (with nods to Ronald Embleton and Walter Crane) for showing me that it’s possible to teach without excluding, and to inspire just by being seen as who and what you are.

Dr Cora Beth Fraser is a lecturer with the Open University. She also writes the Classical Studies Support website, and last year launched the Asterion hub for neurodiversity in Classics.