Rhetoric and Refugees: The Children of Herakles and The Modern Migration Crisis

Aisha Ahmad

Jun 3, 2022

5 min read

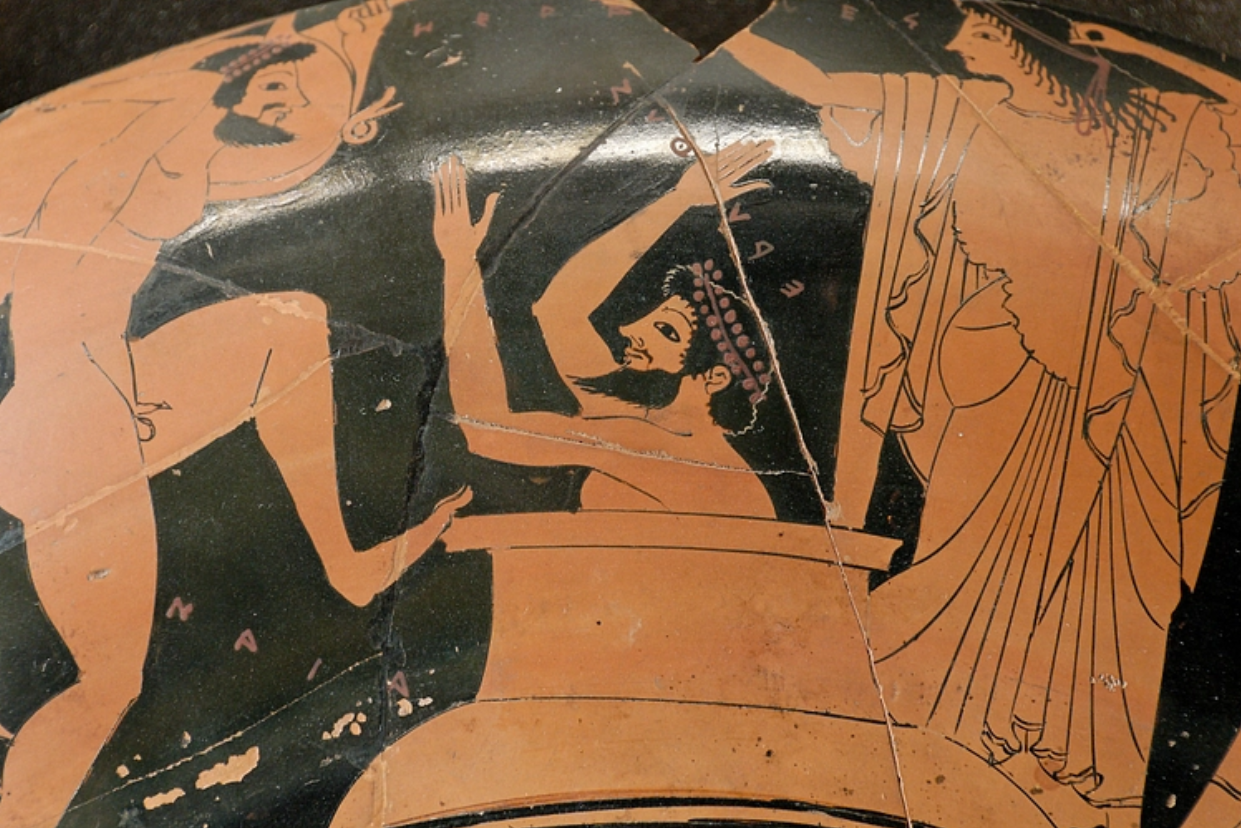

A detail of a red-figure vase showing the king of Argos, Eurystheus, hiding from Herakles. (Louvre Museum, Paris)

If you’ve switched on the news at some point in the last forever, you’ve definitely seen something about a refugee crisis somewhere in the world. Sadly, this isn’t really anything new for human history. Where there are people, there is conflict; where there is conflict, there are refugees. The Classics aren’t particularly bereft either, with myriad ancient plays dealing directly with the age-old question: how far do we help?

Suppliants in Ancient Greece were under the protection of Zeus, and no one really wanted to anger him. He turned you into a cow if he liked you (poor Io). If you messed with philoxenia, the hospitality clause that translates to ‘love of the foreign’, bad things happened to you. To avoid this, if a suppliant showed up at your door, you fed, watered and clothed them (and if they needed a bath, that’s what you had slave women for). You didn’t ask where they came from or what they’d done until after the feasting and quaffing. So if, say, someone had killed your sister who you’d married off to the neighbouring king’s second cousin, and he then showed up to your house literally soaking in her blood, well. Bring out the spit, it’s time for a barbeque!

Euripides’ Children of Herakles has a political twist to it. The play begins at the altar to Zeus at Marathon (so the god is definitely watching), where the eponymous children of Herakles (or Herakleidae), their grandmother Alkmene and their caretaker Iolaus have been driven to by Eurystheus’s dogged Herald. As we know from the twelve labours, King Eurystheus of Mycenae is a particularly petty and cowardly man. Herakles is dead, he thinks, so let’s stone his children to death! Oh, they’ve left Argos because I exiled them? Chase after them!

A Roman fountain mosaic from Anzio depicting the hero Herakles and his faithful companion Iolaus. (Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome)

But they’ve come to Athens, lauded as the most hospitable of all the city states in Greece, or at least that’s what Euripides’ Athens wanted and willed itself to be seen as. More than that, the play’s King Demophon of Athens is blood-related to the children of Herakles, so this is really a matter of honouring blood ties.

This seems like a really smart move on Iolaus’ part: they’re at a sacred place, asking a “nation subordinate to none” for help (Athens now has a reputation to maintain), and they have genealogical ties. Their claim to asylum is strong.

The Herald asks Demophon whether he’s willing to go to war for a bunch of children and an old man that aren’t even theirs. For the aforementioned reasons, Demophon tells him to shove off. And then, of course, war does arrive; Athens marshals her troops and oracles.

And the oracles say that Persephone won’t let them win unless a virgin maiden is sacrificed.

Now, in the play, one of the daughters of Herakles makes a fine point: if I’m going to die either way, I’d rather it be as a sacrifice than as a stoned and/or raped prisoner of Eurystheus. Fair enough. She is sacrificed, one of her brothers returns with an army to help Athens fight the Mycenaeans, they win, Alkmene sentences Eurystheus to death, he dies. All’s well that ends well.

Except the eldest daughter of Herakles didn’t volunteer as soon as the oracle’s figured out the problem.

King Demophon makes a big show of not being bullied by Mycenae and he would happily go to war to prove it, but when the oracles ask for a virgin sacrifice, and his people hear, there are riots. Some said he was right to take in the refugees; others said that he was a fool.

Demophon is faced with a moral dilemma: are these foreign children worth the life of an Athenian child?

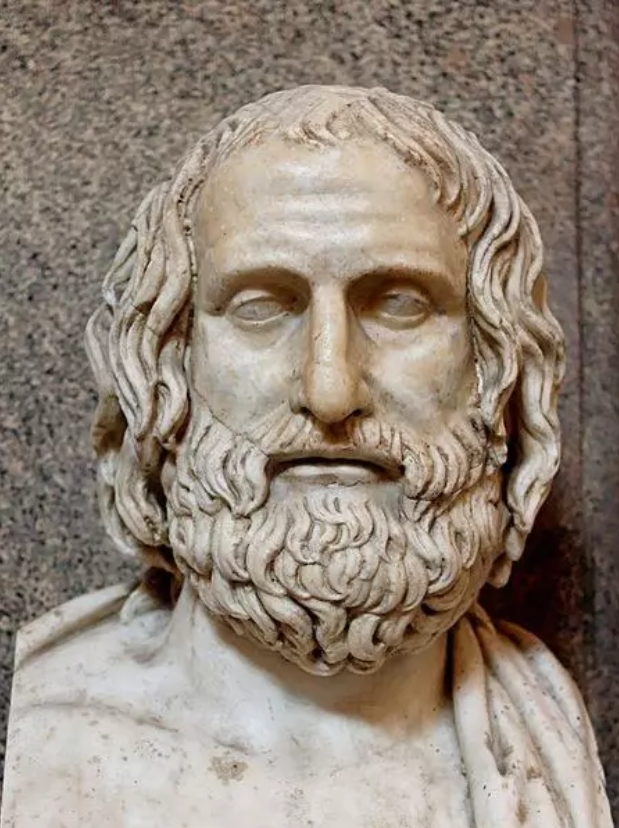

A bust of Greek Tragedian Euripides (c. 484-407 BCE). Roman copy of a 4th century BCE Greek original. (Vatican Museums, Rome)

And it’s a good question, one that today’s politicians still ask as rhetoric. The play itself seems to cop out by having one of the children of Herakles take the fall, and she gives a lovely speech about how it would be a disgrace on her father’s name if they asked for help to the detriment of their benefactors. This implies that if a refugee brings problems with them, they should step up and fix the issues they cause.

And, these days, that sounds familiar.

There is no easy answer to the question, not in The Children of Herakles and certainly not in real life, then or now.

The play ends with Eurystheus’s death, and what should have been a cathartic moment is marred with his rhetoric. He tells the Athenians: one day these children will grow up and they will destroy you. By helping them, you have spelled your doom. Such, he says, is the “nature of these strangers whose lives you have saved today”.

In 2016, Nigel Farage said that vetting the Syrian refugees was necessary, or who knew who could be a jihadist, could be a threat to our people. The UKIP party rhetoric was: our schools are being flooded and our hospitals overburdened by economic migrants and we really need to stop that. They really, it was implied, ought to fix their own countries instead of coming here for a better life. Reports of atrocities committed in Greece against refugees have been coming in for the better part of a decade: deliberate starvation, gross overcrowding in refugee camps both on the islands and the mainland, pushing people back into the sea ad nauseam. And now in 2022, the UK government has decided to only take in Ukrainian refugees that are related to British citizens.

The Children of Herakles was performed in 430 BC, and nearly 1600 years on, the rhetoric hasn’t actually evolved much. The question of how far and to what extent a suppliant can be helped, and which is the “right sort” of suppliant, isn’t an easy one to answer, but it is certainly a universal one.

In the play, Athens had a duty to take in its suppliants and were rewarded with the promise of friendship with the Herakleidae. Eurystheus said Athens was naïve.

Politics does not exist in a vacuum, and Athenian politics in 430 BC are certainly not comparable to modern day globalised politics. And, of course, Herakles isn’t real.

But what is comparable is the spirit of the rhetoric: us versus them, ours versus theirs, the line between generosity and self-destruction.

People are divided today, just as the Athenians were in this play, over whether taking in suppliants is folly or righteous.

There certainly isn’t a right or wrong to be had here (you know, except pushing people into the Aegean sea so they don’t have to be your problem, Greece*), but philoxenia, though ancient, has been a core principle of European culture for a long time. It must be noted though that Athens didn’t have an issue with the children of Herakles until they were threatened with the idea of the death of one of their own. So maybe the issue then isn’t the refugees at all; maybe thinking of them as a threat is.

* The reports of border patrols on Greek shores pushing migrant boats back “to Turkey” have been ongoing in fairly mainstream media since 2020. The Greek government denies the claims, saying that they have a strong “tough but fair” strategy to deal with the refugee crisis.

LAST-MINUTE EXILE: AISHA AHMAD

Hometown: Boston, Lincolnshire

High School: Boston High School

Like Seneca, like Aristotle, and like countless others from Classical history, you find yourself subject to an exile order, and must vacate the country tout-suite before some sort of sword-based injury befalls your neck!

You grab three records…

1. Can the entire Hamilton soundtrack count as one record? Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Stories is my favourite.

2. Pompeii or Icarus by Bastille

3. Period by Chemistry

…two books…

Only two??? Well, Ovid’s Metamorphosis because Ovid is love, Ovid is life.

Probably a language primer for wherever I’m going to end up, if I’m being practical about this. If not, Mahmoud Darwish’s In the Presence of Absence. An exile anthology for an exile.

…a Tupperware of your favourite food…

A box full of watermelons. Or skip the box, just a watermelon.

…and something else at random.

A convincing disguise – maybe a wig or a fake moustache. You know, to dodge security cameras.