The Key to Unlocking Classical Architecture: The De Architectura of Vitruvius

Jackson Dugan

Jun 4, 2022

3 min read

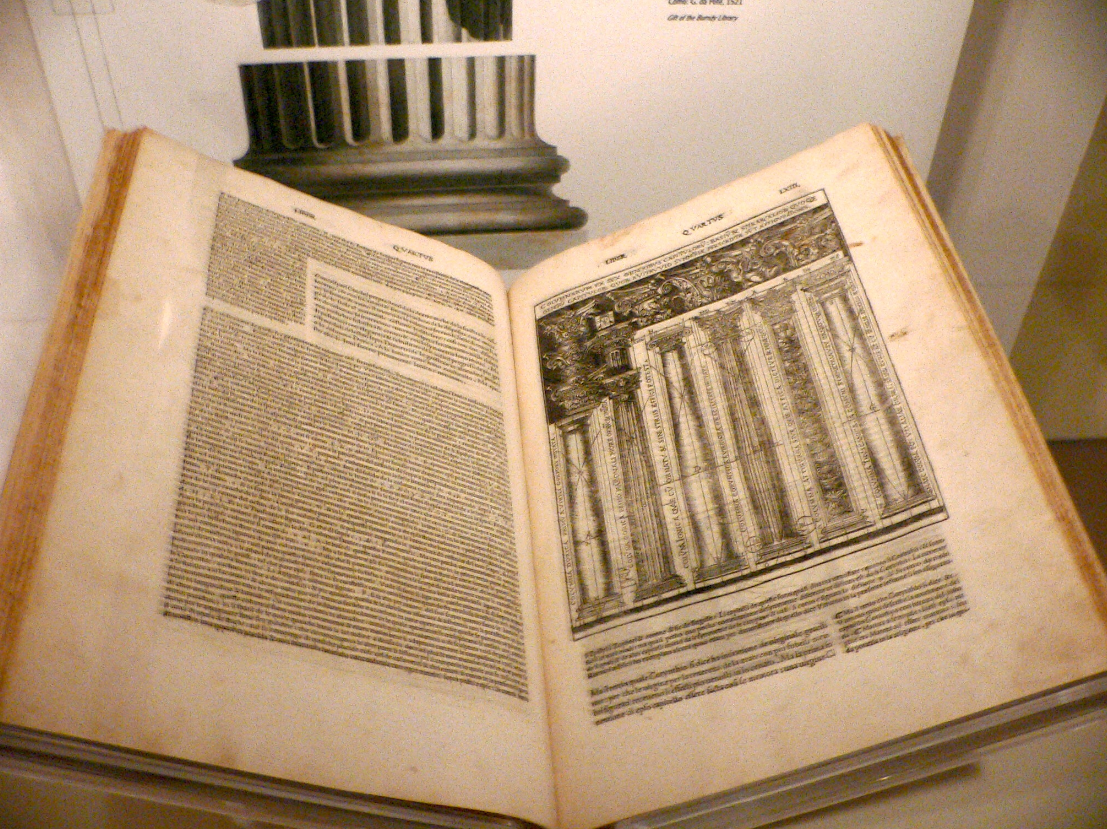

A 1521 Italian language edition of De architectura, translated and illustrated by Cesare Cesariano.

Classical architecture is one of the most widely recognizable architectural styles in the western world and continues to be a dominant style thousands of years from its origin. Today, the likeness of Greek and Roman temples is seen most often on modern government buildings and museums; the Classical portico remains an architectural staple.

How is it that a style with origins thousand years in the past could still be so present?

We are fortunate to have so many ancient buildings still standing today, two thousand years after their construction. Some are preserved so well that one might even question that the building is so old – the Maison Carrée in Nîmes is an excellent example. However, only so much can be learned through observation of a structure, and the state of ruin of a building only increases the difficulty of understanding the architecture. The information that we cannot take from extant buildings can be found in written texts about architecture. As the only surviving architectural treatise from antiquity, De Architectura is the absolute authority on classical architecture.

Like many antiquities, provenance is not entirely certain. Vitruvius’ qualifications and involvement in certain things are questioned by some, but the knowledge evident in his work is certain. De Architectura was written in the first century B.C. and was dedicated to the emperor Augustus; many scholars believe that Vitruvius served the emperor directly. There are several known structures believed to have been built by Vitruvius, but the evidence is not convincing. Almost all the information about him exists in his surviving treatise, De Architectura. The treatise comprises ten books and covers more than just architecture; sundials, mechanics, and military engineering also feature, demonstrating the author’s impressive and broad knowledge.

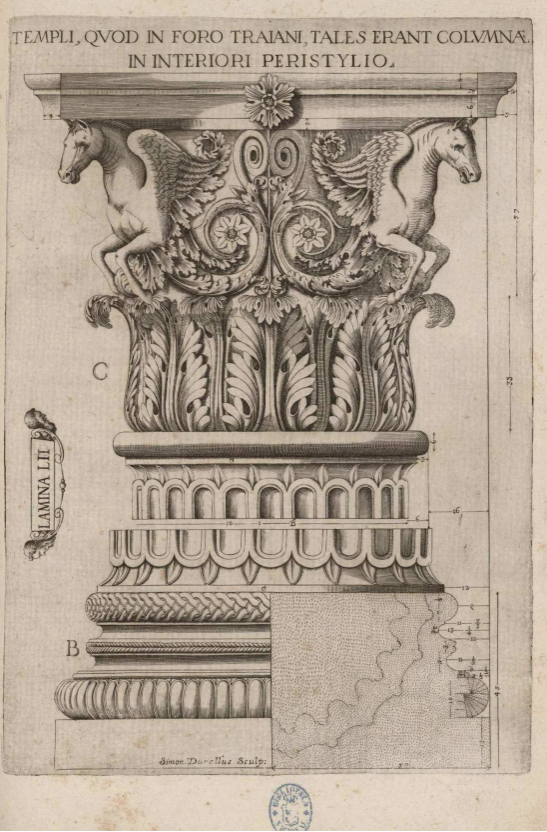

Civil architecture, right and oblique: Simon Durellius engraved. Biblioteca Nacional de España

The text was known in the Middle Ages but served merely as a historical document and was not considered a major work of architectural theory (a shame). In the fifteenth century, De Architectura was rediscovered in a Swiss library by an Italian scholar named Poggio Bracciolini. The treatise was then printed and circulated widely among the great architectural minds of the Renaissance at a time when interest in classical studies – particularly in art and architecture – was surging. For the rediscovery to occur during a period of heightened interest in Classics meant that De Architectura was not simply a historical document, but a one-of-a-kind primary source for the understanding of classical architecture. Understanding and translating Vitruvius’ text was a challenge, as it contained a mix of specific Latin and Greek architectural terminology, but that did not deter scholars from tackling the ancient text.

The ancient treatise inspired a mass of classical architectural treatises to be written and published during the Renaissance with specific connections to and interpretation of Vitruvius’ work. These new treatises made clearer the complex specifics of aedificatio, or the science of building, to contemporary architects and builders and this allowed the classical style of architecture to flourish in the latter portions of the Renaissance. English translations of Renaissance treatises began to circulate in the eighteenth century, prompting a rise in classical revival architecture among the English elite. The federal style of the United States of America is a direct line from Vitruvius. Thomas Jefferson, one of the main forces behind the development of this style in the U.S., used Andrea Palladio’s sixteenth century treatise as a guide; Palladio stated Vitruvius’ text to be his master and guide.

To have a text as complete as De Architectura surviving from antiquity is incredibly important for the understanding of the classical style. Understanding classical architecture in ancient writing is invaluable as it provides insight into the vision and processes of those who designed and built the ancient structures themselves. The scholarly work done in the Renaissance to further the understanding of the classical style made it more accessible to people for the next several hundred years. Without the rediscovery of Vitruvius’ text, the puzzle of understanding classical architecture would be far more difficult as the details within the text cannot be understood simply by studying ancient ruins.

In addition to the active processes that contributed to the persistence of the classical style, the fundamental principles of the architecture are timeless. Simplicity, proportion, and numeric harmony are some of its principal elements. The proportionality of the classical orders is modeled after the proportions of the human body – natural beauty. These basic elements are so in tune with science and nature, and that is a very important factor in the ever-lasting beauty and functionality of classical architecture.

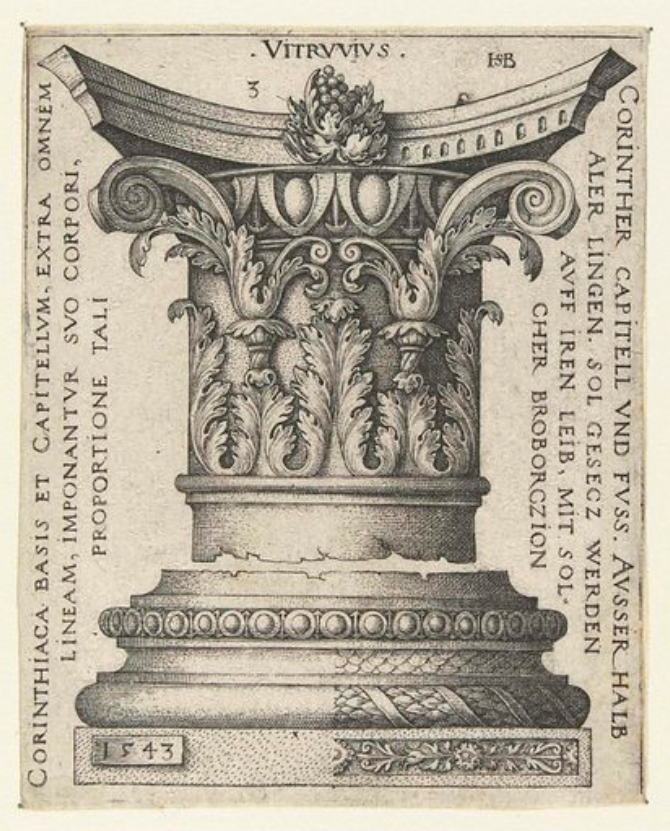

Design for the base and capital of a Corinthian column; with leaf ornaments on the capital. 1543 Engraving © The Trustees of the British Museum

Jackson Dugan (he/him) is currently completing an undergraduate degree at Santa Clara University, studying Psychology, History, and Art History.

"History has always fascinated me, and at university I have had the opportunity to study the art and architecture of ancient Greece and Rome, which has produced in me a growing interest in classical studies."